This post follows on from I – Murder at Mount Magnet and II – A Suspect Emerges

Not much had changed in two years. The investigation into the Mount Magnet murder had ground to a halt. The police had not been able to identify the victim and they had not been able to identify the perpetrator. North of the town the Rose Pearl continued to sit abandoned save for a few old prospectors. It held fast to the truth surrounding the crime but still had one last secret to share.

At 5pm on 17 November 1902, Reuben Brooker and Charles Pollock were trying their luck prospecting in one of the old shafts known as the Black Swan. Reuben went down into the mine shaft and at the bottom (60 feet) began the task of removing earth which was blocking a drive. While doing so he came across a rotting chaff bag tied with a piece of lace. The ominous odour arising from the bag was enough to convince him to send it up to Charles.

On the surface Reuben and Charles examined the bag and decided to open it. Inside were bones consisting of a pelvis and the lower portion of a spine. Closing the bag back up, they left the mine and returned to Mount Magnet. At 8pm they arrived at the police station and handed the bag and its contents over to Corporal John Blain (previously Constable in Part II) and Constable Edward Campbell.

Constable Campbell took the bag and the remains to the Mount Magnet Hospital so that Doctor Charles Willis could provide his professional opinion. Dr Willis carefully looked over the bones, placed them back together and declared that they were “…the lower portion of the trunk of a Human Skeleton.“

Corporal Blain quickly came to the conclusion that the remains most likely belonged to the man who had been murdered in 1898.

…is believed to be the missing part of the dissected remains of a man who was found murdered and thrown down two other abandoned shafts known as the Rose Pearl Mine near four years ago.

The next day the police travelled to the Black Swan shaft and carried out a thorough search. They found a spinal joint which was presumed to have fallen out of the bag but otherwise found nothing else. There were no new clues to add to the case.

Like all the other mine shafts in the area, the Black Swan had been searched in 1898 however it was noted that the police had only used a glass to help them see the bottom of the shaft. They had not gone down into it to investigate and thus did not see the bag. It had likely been thrown down by the perpetrator and rolled out of sight once it hit a slope at the bottom.

With official advice stating that an inquest was not necessary, the final part of the man’s remains was buried in Mount Magnet cemetery with the rest of the body.

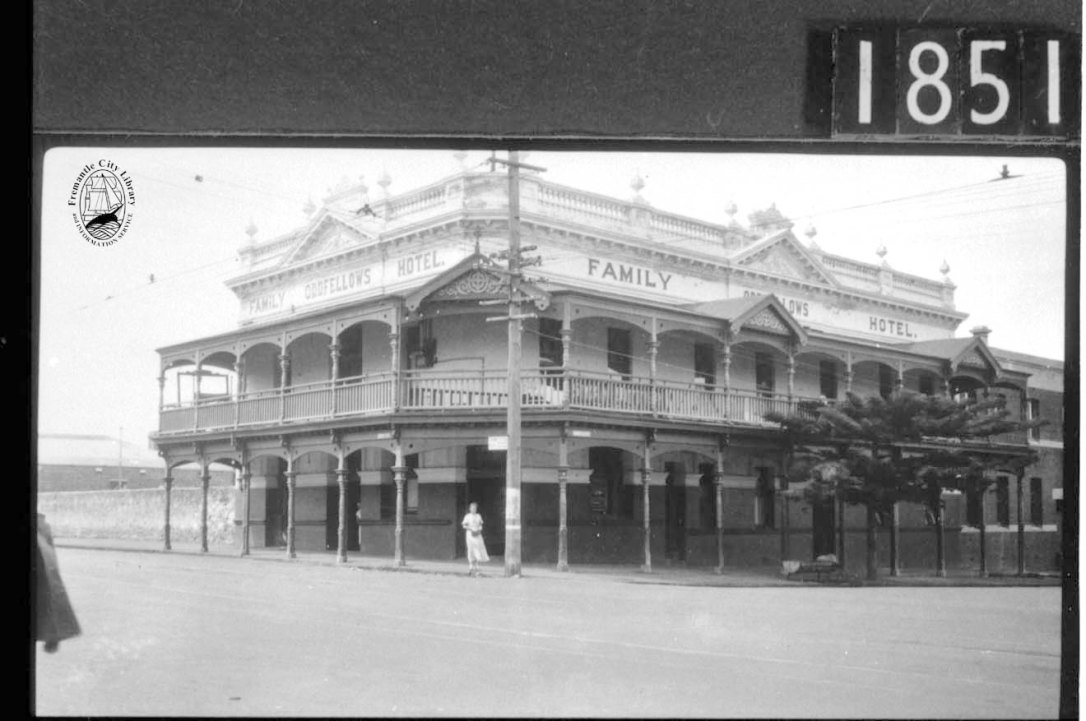

Coincidentally, in Fremantle on 19 November 1902 (two days after the remains were found) Fontain lost his temper with two men named Anthony Murray and John Keffar. The men had visited Fontain’s brothel on Suffolk Street and were kicked out after an altercation. They then attempted to gain admittance to the brothel next door by smashing the door down. Fontain emerged from his house, took aim with his revolver and shot at them. They escaped injury and quickly headed to South Terrace, walking towards the Oddfellow’s Hotel (today the Norfolk Hotel). As they neared the Hotel, Fontain appeared at an alleyway, stepped in front of them and said “You —–, I have got you now!” He again fired at them and found his mark, putting a bullet through Murray’s left hand.

Fontain went back to the house on Suffolk Street and the matter was soon reported to the police. Interviews revealed that Keffar had actually stolen something from one of the women and he was charged with theft. Sergeant John Byrne (Constable in Part II) then charged Fontain with shooting Murray with the intent of doing grievous bodily harm.

Finally the police had him where they wanted him. On 27 November Fontain faced the Fremantle Police Court. Evidence of a gun found on the premises was not enough so the police relied heavily on the witness statement of Murray. Fontain reserved his defence and was committed for trial. Bail was fixed at £100 for Fontain and £100 for an independent surety who made sure he attended Court.

On 17 December 1902, Fontain appeared before the Supreme Court in Perth to answer the charge. Before proceedings got underway the Crown Solicitor (Mr Burnside) stated to the Commissioner that he wanted to call his witness (Murray) because he had reason to believe that he would not answer. Murray was called and did not appear.

It was thought that Murray was either keeping out of the way or had left Western Australia. Without the main witness the Crown chose to abandon the case. Once again Fontain managed to escape prosecution.

Not completely having done with the Courts, on Christmas Eve Fontain was back before the Fremantle Police Court charged with assault by his wife Marie Fontain (Sweet Marie). They had only been married for two years and decided on a judicial separation without maintenance. The charge of assault was put aside.

Peter Fontan (38) was proceeded against by his wife, Marie Fontan, who asked for a separation order, in consequence of the defendant’s persistent cruelty.

Despite the shooting case being abandoned, talk of Murray’s disappearance intensified and word soon spread that it was a direct result of Fontain’s influence. The fact that he had used his power and wealth to evade the law was not lost on the press. Where the police and mainstream newspapers would not (or could not) tread, the “gutter” press had a field day.

Described as “one of the most dangerous and loathsome ruffians in the country“, Fontain was said to have arrived in Western Australia from Europe via New Caledonia in the 1890s. He soon set up business as a bludger (the Victorian era word for pimp) and had houses in Geraldton, Mount Magnet, Lennonville, Cue, Nannine, Leonora, Menzies, Fremantle and Perth. Hinting that he was wanted by the police for a lot more than just operating a brothel, The Sun stated, “…unsuccessful attempts have been made by the police to “pot” him on charges even more serious than his vile traffic in the bodies of his countrywomen.“

…Fontan is a man of ungovernable temper, who will shoot at a man or knock about one of the wretched women who are in thrall to him with equal readiness.

It was apparently not the first time he had paid off witnesses who were meant to testify against him. The writer mused that “…Till he gets his deserts, he will be a menace to the community.” Perhaps sensing that the tide had turned against him, Fontain was said to have left Western Australia for France on board the German mail steamer Barbarossa.

As was the case in 1899 (and perhaps because Fontain was away) people once more began to talk. On 10 January 1903 Constable Joseph Creeper of Cue wrote a report in relation to the Mount Magnet murder. He had been talking to a woman (her name was kept secret due to her ill health) who said that Sweet Marie “…was frightened that her husband Peter Fontain would some day murder her as he had done to a man at Mt Magnet some three years ago.” The woman went on to say that Sweet Marie described the murder to her.

…the man had been first hit over the head and when found to be seriously injured had been murdered and his body cut up and distributed in the old Shafts in the neighbourhood…

In a statement greatly resembling the words of Victor de Cosson, Sweet Marie claimed that if she had police protection, she would confess all she knew about the Mount Magnet murder as well as the other murders (supposedly three) committed by Fontain.

Constable Creeper spoke to another prostitute named Rose Austin (alias Topping) who believed that a French prostitute named ‘Mignon’ had a letter from a witness relating to the Fremantle shooting case. It was noted that both Murray and Keffar were paid £150 each by Fontain and were told to get on the next ship to New South Wales. In his letter, the witness expressed remorse at having accepted the bribe.

Rose also mentioned the death of Ernest Salvator in Menzies. Mignon had told her that Ernest had not committed suicide. Fontain had shot him inside the brothel, moved his body, positioned him on the toilet and then placed the gun in such a way so as to make it look as though he committed suicide.

Almost everything about Ernest’s death indicates that he did commit suicide. There is however one piece of information which does not quite fit. The Doctor noted in the inquest that he found splinters of wood on Ernest’s brain. He could not explain how they got there. It is perhaps the tiniest of clues to indicate that not all was as it seemed.

Summing up his report, Constable Creeper advised that Mignon was en route to Suffolk Street in Fremantle and was expected to arrive on 12 January. He suggested both Mignon and Sweet Marie be interviewed and was confident they would tell the police everything.

…this woman is a terror as is also Marie Fontain of Peter Fontain and I believe that if taken carefully both would give evidence which would be the means of convicting the man Fontain of more than one murder in this State.

As he was already familiar with the case, Detective Stephen Condon was instructed to undertake the inquiries. He interviewed both women and wrote a report on 22 January.

From Sweet Marie he got nothing. She denied having talked to anyone about the murder. She remembered the body being found at Mount Magnet but knew nothing about it. She had been questioned numerous times by the police because they believed Fontain was involved but said they had no proof. According to Sweet Marie, Fontain had nothing to do with it and was in Albany when the murder was committed. Detective Condon noted that it was an interesting statement to make considering no one could confidently confirm when the murder was committed.

On the other hand Mignon (whose real name was Amelia Vasseur) was perfectly happy to talk to Detective Condon and gave a statement at her camp near the Smelting Works in South Fremantle.

She stated that in about September 1898 she took over Fontain and Sweet Marie’s hessian camp at Mount Magnet. At the time they had relocated to Cue and in November the same year, the dismembered body parts of a man were found in various mine shafts of the Rose Pearl. Nobody (including herself) knew who the murdered man was.

From Mount Magnet she moved to Cue and then on to Nannine. On one occasion when visiting in Cue she witnessed a violent fight between Sweet Marie and Fontain.

She [Sweet Marie] accused him of having committed a murder and that she could gaol him and hang him. She didn’t mention who he had murdered. Fontan gave her a terrible hiding and tried to shoot her and would have done so only she managed to get out of his sight.

Mignon was also in Cue in November 1902 during the time Fontain was charged with shooting Murray. She spoke to Sweet Marie who said in relation to his predicament, “Oh I don’t care, he has bloody luck, he has killed two fellows already and never done Gaol.” Sweet Marie claimed she would not help him but then changed her mind the next day and left Cue for Fremantle. Mignon denied having ever received a letter from Murray however she was told that Fontain had given him £25 to leave Western Australia before the case went to Court.

The conversation then turned towards the murders. Around the same period of time (November 1902) Mignon spoke to a well-dressed commercial traveller who told her the story of Ernest Salvator’s death and how it was made to look like suicide. That same story was also recounted to her by an Italian teamster. She said there were rumours that Fontain had committed a third murder but she could not remember where it was said to have occurred. She gave a simple statement with regards to the Mount Magnet murder.

It was generally believed at Mt Magnet and Cue at the time the body was found cut up that Fontan done the murder.

Like many of the other people who dealt with Fontain, Mignon was afraid of him. She confirmed that Sweet Marie was also frightened and that it was this fear which stopped her from coming forward. Mignon stated, “I am sure Fontan is a murderer. I don’t think any one but Marie knows about the Magnet Murder.” If that was the case Sweet Marie’s fear may not have been of Fontain alone. She may have also been afraid for herself, especially if she was somehow involved in the murder or the disposal of the remains.

Fontan knows well that he is suspected of this murder and laughs at the idea. [Detective Condon]

Constable Creeper was instructed to find out more information in Cue and by February 1903 he forwarded a statement from John Sears who was the licensee of the Federal Hotel.

John Sears stated that Sweet Marie had on occasion boarded at the Federal Hotel and during conversation (usually when she was drunk) he heard her divulge that Fontain murdered the man at Mount Magnet in 1898.

Matching the unidentified woman’s statement from earlier in the year, Sweet Marie went on to say that the man had created a disturbance in her house and refused to leave. Losing his temper, Fontain hit him over the head with a stick and as the man was found to be badly hurt, decided to kill him. He then dismembered the body, carried the parts away and threw them down various mine shafts.

Indicating that the murder had taken place inside her home, Sweet Marie stated that the blood stained floor of the kitchen was removed and subsequently burnt to hide the evidence of what had occurred.

Mr Sears asked Sweet Marie if she would go to the police with what she knew and she responded that she would not because she was too scared of Fontain. She said that he had killed a man (referring to Ernest Salvator) and positioned him on the toilet to look like he had committed suicide. He had also murdered another man and got away with it.

Interestingly, Louis Trait (on bad terms with Alfred Anderson and mentioned in Part II) was brought up by Mr Sears. Trait was never interviewed by the police but apparently knew about the murder.

…[Trait] mentioned that he could give a lot of information concerning the Mt Magnet Murder if the reward was large enough.

Despite the implicating statements it was not enough to be used as evidence. Nothing more came of the police investigation and the file was returned to Perth. Where the police records end, the newspaper reports take over.

In February 1903 Sweet Marie was one of eight French people on a picnic at Smiths Mill (today Glen Forrest) when vigneron, Charles Lauffer, was killed. All were charged with murder and at the end of the trial, six (including Sweet Marie) were found guilty and sentenced to death. They appealed and in April the judgement and the verdict were set aside and five of them (again including Sweet Marie) were acquitted. The one man found guilty (Frederick Maillat) was hanged. While I won’t go into detail about the case, it seems Sweet Marie’s involvement was enough to cause the Mount Magnet murder to be rehashed in the press.

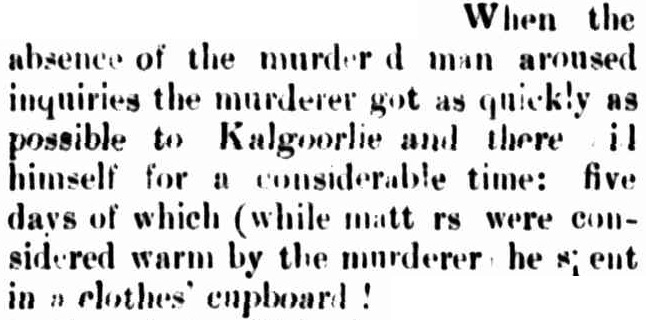

The Spectator (Perth) got almost all of the details relating to the finding of the remains wrong however they went on to say that the man who “mysteriously and very suddenly” disappeared was lured to the brothel, robbed and murdered. His body was then cut up and distributed among nearby mine shafts. To cover the crime, the house was dismantled and refitted and the floor removed and burned (matching Mr Sears’ statement).

Picking up on the story, The Mt Leonora Miner printed the recollections of people in Leonora. Similarly, it was said the man (in possession of £60) was convinced to enter the brothel where an argument later occurred and he was murdered. The body was cut up, the head burned (a statement I’m inclined to question) and the parts thrown down various mine shafts. They also printed details of the perpetrator’s reaction once the police were involved although it could simply be a work of fiction intended to paint him as cowardly.

The Evening Star (Boulder) did not dance around the subject and was more direct than the aforementioned papers.

There is little doubt that the woman Fontan and her paramour, who has gone to France, were the murderers of the man whose remains were found at Magnet…

For the next five years the Mount Magnet murder remained absent from the newspapers. When the story was revived in 1908 it was because of a court case in South Australia.

John Smith was from Narracoorte in South Australia and was aged about 46 when he decided to give up farming and try his luck on the goldfields of Western Australia. He arrived in 1898 and in June was known to be in Mount Magnet. He wrote regularly to his family but stopped after arriving in the town. Concerned, and with John’s father sick, they attempted to track him down. Notices were placed in several newspapers in February 1899 asking for information.

They never heard from him again and they never heard from anyone with information about him. John’s father died in 1899 leaving a significant Estate to be divided between John and his sister. Ten years after he left as a prospector, John Smith was officially declared dead by the Adelaide High Court and his sister inherited the whole of the Estate.

A writer for The Sun (Kalgoorlie) was investigating John Smith’s disappearance and noticed a connection between the time John disappeared and the time the remains were found. He wrote a letter to a member of the family and included a description of the deceased man. They responded that they were “only too sure” that the man found dismembered was John Smith.

A description of John was provided by the family and it matched the height, hair colour and teeth of the deceased. With John known to travel with hundreds of pounds in his pocket, it was presumed that the motive for the murder was money.

The Sun certainly made a convincing case. The likelihood of the deceased man being John Smith is strong however without any evidence found with the man’s remains there is still the chance that it was not him at all. There is no doubt that John disappeared after 1898 but there is the possibility that something else had befallen him.

I am also puzzled by the fact that he had friends on the goldfields, people he visited and people he knew. Why, when police were seeking information about missing people, did no one come forward with information or concern for his welfare? Did they simply presume he was alive and well? Why was he never a possibility in the police investigation when notices were clearly printed in several newspapers indicating that no one knew where he was.

No major Western Australian newspaper reprinted the story and the police did not look into the possibility of John Smith being the deceased man. Such lack of action when The Sun was so confident shows just how hopeless the prospect of identification was. Perhaps with the aid of modern technology answers would have been more forthcoming.

As the gold rush days continued to slow down the Mount Magnet murder further disappeared from public knowledge. It was assigned to memories; brought up during different periods of time as part of nostalgia articles written by people who once lived in the towns and prospected on the fields. The gist of the story remained the same however there were some inaccuracies which likely arose from the passing of time and the story changing slightly whenever it was discussed.

In 1937 ‘Waramboo‘ of Southern Cross wrote a letter to ‘The Dolly Pot‘ section of the Western Mail stating that he thought it was strange that the murder was never solved. He recounted the finding of the remains and added further information which he heard from Wilton Hack, Theo Hack and George Dent who were friends of John Smith’s. They never heard from John after they left him at the Mount Magnet train station and when the remains were uncovered, they viewed them and could “positively recognise” the head as being John’s.

To return to 1898, Corporal Pilkington actually did speak to one of the Hack brothers when he was trying to locate John Brockelbank (mentioned in Part I). Despite this and the strong assurance written in the 1937 article, there is nothing in the records to indicate that the Hacks told the police they were sure the deceased man was John.

The writer also described an incident at Connie Drew’s Diamond Jubilee Hotel which involved (I assume) Fontain (left). The incident certainly matches what we know of Fontain’s behaviour however I am a little sceptical that even he would brandish a knife in a hotel in front of a crowd of people.

The writer also described an incident at Connie Drew’s Diamond Jubilee Hotel which involved (I assume) Fontain (left). The incident certainly matches what we know of Fontain’s behaviour however I am a little sceptical that even he would brandish a knife in a hotel in front of a crowd of people.

Finally, in 1951 a ‘Murchisonite‘ told a similar story to ‘Waramboo’s‘ under the ‘Westraliana‘ section of the Western Mail. The murder was noted to be unsolved despite a thorough police investigation and went…

…down in West Australian criminal history as one of the State’s greatest mysteries.

![]()

There is much about this story that we will never know for sure but in looking over the records we can get as close as possible to some semblance of the truth. What we know absolutely is that a man was hit over the head, dismembered and thrown down various mine shafts in 1898. The rest can only be deduced. Weighing up the evidence; the police records, the statements given by numerous people and the newspaper reports, it is fair to assume that Pierre Fontain and even Sweet Marie were somehow involved in the murder at Mount Magnet.

What is apparent is that it was not Fontain’s only foray into the world of crime. He was likely once a convict from New Caledonia who became a bludger in Western Australia and lived off the proceeds of prostitution. He was a violent, angry man who had an attitude of ‘shoot first ask questions later’ whenever he felt he had been wronged in some way. Perhaps it was that attitude which resulted in the murder of more than one man.

The suicide of Ernest Salvator has a rather large question mark hanging over it. Police were ultimately convinced that the inquest verdict was correct however the statements made years later as well as the splinters of wood found on Ernest’s brain are enough to make me question Fontain’s version of events. Were the stories a fabrication stemming from an overexcited public’s imagination or did they actually hold some truth?

Curiously, in the Mount Magnet records is a file dated 1896. It contains police documents relating to the finding of skeletal remains at the bottom of the abandoned Elvira shaft near Coolgardie. The remains were of a man and a large hole on the right side of his skull indicated that he had been violently hit over the head. An inquest later found that he had been murdered. Neither the victim nor the perpetrator were identified. The case was unsolved and there was nothing to show Fontain was involved however the fact that it was placed within the Mount Magnet file suggests that the police had their suspicions. Was this the third murder thought to have been committed by Fontain?

Frustratingly, what became of Fontain after 1902 is unknown. Records state that on 31 December 1902 he left Western Australia for France on board the I.G.M.S. Barbarossa however his name does not appear on the passenger list. He may have been using an alias (something he was known to do) or he may not have been on the ship at all. Perhaps he stowed away or left on a different ship altogether.

Later newspaper articles stated (albeit vaguely) that the man who committed the Mount Magnet murder was hanged for the murder of Charles Lauffer. For this to work it would mean that Fontain was using the name Frederick Maillat as an alias and (remarkably) no one at the time recognised or identified him. Maillat and Fontain were both French, both connected to Sweet Marie, both tall and both considered to be very good looking. There was however a ten year age difference. Apart from the similarities, there is nothing else which ties them together. I do not believe Fontain and Maillat were the same person. There is no clear answer as to what happened to Fontain however after 1902 he no longer appears in the newspapers. It is a fact I’m inclined to assume means: he left Western Australia for good.

Sweet Marie however remained in Western Australia. Having escaped the death penalty in 1903 she promised to turn over a new leaf but soon returned to her old ways. She travelled around much like she did with Fontain and was recorded over the years as living (and causing trouble) in Broome, Fremantle, Leonora and Kalgoorlie. Whatever she knew about the Mount Magnet murder was never divulged to the police. As early as 1902 it was noted that she had become addicted to vermouth and as the years rolled by her alcoholism worsened. Perhaps she drank to forget. On 5 May 1914 Marie Fontain died from cirrhosis of the liver at Kalgoorlie Hospital. She was only 39.

While there is a large amount of information pointing towards Fontain as the perpetrator, there is not a lot of information pointing towards the identity of the victim. The Sun’s investigative reporter probably had the best possibility in their article about John Smith however I still hesitate in stating it was him. I can’t imagine Fontain would need to rob anyone (unless it was done after the murder) so it seems likely that the story Sweet Marie told may have been what occurred. A man was hit over the head during an argument and then murdered. Was that man John Smith? Much like Fontain’s whereabouts, it is a question which may never be confidently answered.

It is natural for people to take delight in stories with positive endings; good guys prevailing and the evil in the world facing their just deserts. It is a sad fact of reality that not all stories end that way. Not all criminals face punishment and not all victims receive justice. The mystery of the man who was murdered at Mount Magnet will likely persist for all time. I don’t presume to have given him any sort of justice but I hope that by researching and writing the story in its entirety that I have at least put out there for him, something of the truth.

Sources:

- State Records Office of Western Australia; Western Australian Police Department; Crown Law – remains found in abandoned shaft, Mount Magnet; Reference: AU WA S76- cons430 1902/5032.

- 1902 ‘The Mt. Magnet Mystery.’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 22 November, p. 2. , viewed 17 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155983544

- 1905 ‘No title’, Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), 16 September, p. 28. , viewed 18 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33514896

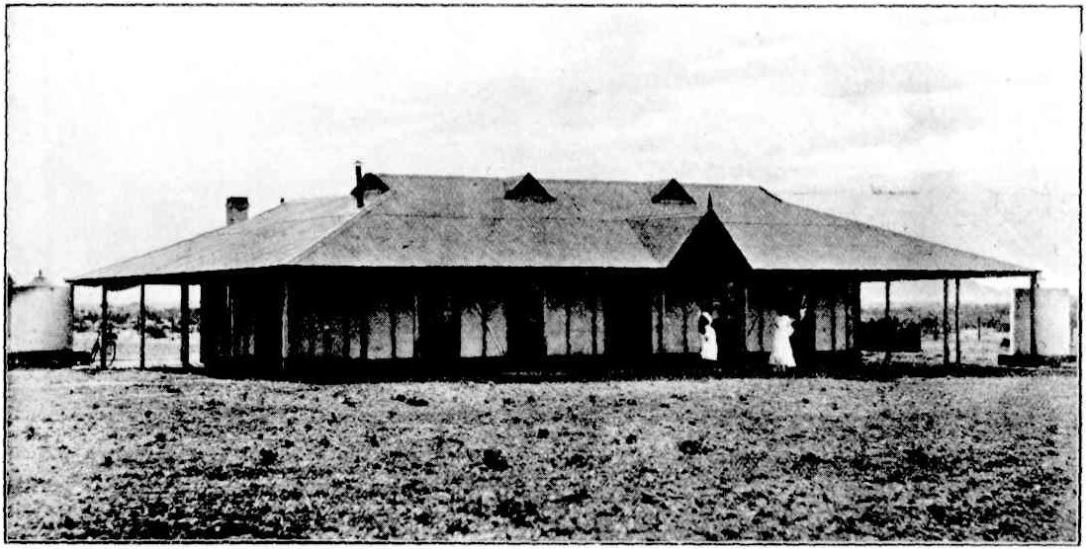

- Image of Mount Magnet in 1900 courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia; Call Number: 090659PD.

- Fremantle History Centre; The Oddfellows Hotel, South Terrace; 1935; Reference: 1851; https://fremantle.spydus.com/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/ENQ/OPAC/ARCENQ?RNI=71461

- Image of the Fremantle Smelting Works in 1920 courtesy of the Fremantle History Centre; Reference Number: 1662; Record Number: 70813; https://fremantle.spydus.com/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/ENQ/OPAC/ARCENQ?RNI=70813

- Image of the hessian camp at Cue circa 1905 courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia; Call Number: 006447PD

- Image of Austin Street in Cue courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia; Austin Street, Cue W.A.; Call number: 013937D.

- 1902 ‘SHOOTING AFFRAY AT FREM[?]E.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 20 November, p. 5. , viewed 17 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article24848380

- 1902 ‘MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCE.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 17 December, p. 1. , viewed 18 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article81323252

- Record of Court Cases, 1861 – 1914 (V23); Ancestry.com. Western Australia, Australia, Convict Records, 1846-1930 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: Convict Records. State Records Office of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia.

- 1902 ‘GENERAL NEWS.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 24 December, p. 1. , viewed 18 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article81319142

- 1902 ‘POLICE COURTS’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 25 December, p. 7. , viewed 18 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article24851088

- 1899 ‘THE MENZIE[?] TRAGEDY.’, The Menzies Miner (WA : 1896 – 1901), 7 October, p. 16. , viewed 22 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article233069217

- 1902 ‘A FRACAS AT FREMANTLE.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 19 November, p. 5. , viewed 25 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article81324827

- 1903 ‘A DANGEROUS CRIMINAL.’, The Sun (Kalgoorlie, WA : 1898 – 1919), 4 January, p. 1. , viewed 25 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211103474

- State Library of Western Australia; The Spectator (1900-1905); EF 994.1 SPE; 14 March 1903.

- 1903 ‘Local and General News.’, The Mt. Leonora Miner (WA : 1899 – 1910), 21 March, p. 2. , viewed 31 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article233202509

- 1903 ‘SM[?]H’S MILL MURDER.’, The Evening Star (Boulder, WA : 1898 – 1921), 17 March, p. 2. , viewed 31 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article203493631

- 1899 ‘General News.’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 25 February, p. 2. , viewed 31 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155979142

- 1908 ‘JOHN SMITH, OF NARRACOORTE.’, The Sun (Kalgoorlie, WA : 1898 – 1919), 15 November, p. 6. , viewed 31 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211768198

- 1908 ‘RELATIVES ACCEPT THE EVIDENCE’, The Sun (Kalgoorlie, WA : 1898 – 1919), 15 November, p. 6. , viewed 31 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211768199

- 1908 ‘HOW JOHN SMITH DISAPPEARED’, The Sun (Kalgoorlie, WA : 1898 – 1919), 15 November, p. 6. , viewed 31 Mar 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211768197

- 1937 ‘Early Mt. Magnet.’, Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), 23 December, p. 11. , viewed 02 Apr 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37845105

- 1951 ‘Murchisonite recalls a grim story Mt. Magnet Murder’, Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), 1 November, p. 18. , viewed 01 Apr 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article52181248

A great yarn. Well written and intriguing.

LikeLike

Thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Very Interesting well written shame there was no out come😀😀

LikeLike

Thank you Sandra. Yes, it is a pity.

LikeLike

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2018/04/friday-fossicking-20th-april-2018.html

Thank you, Chris

LikeLike

Thanks Chris. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed this I am the the great granddaughter of Charles Lauffer am I able to purchase this beautiful book

The dusty box

LikeLike

Thank you Maureen. The Mount Magnet story is only available on the blog in the three parts, but perhaps I should look into publishing it as a book. Glad you enjoyed the story.

LikeLike

Maureen – can you email me – aidan.kelly@iinet.net.au – I am presenting a story on Charles from the angle of the French if you care to swap notes?

LikeLike