The sudden deaths of two people who were said to have been perfectly healthy sent rumours swirling. Bubonic plague was reported in Perth and Fremantle in January and February 1906. Had “the much-feared disease” made its way to the port town? The Geraldton Express was the first to ask the question.

An interview with the Resident Medical Officer was requested and he willingly obliged. Dr Lancelot Hungerford’s response was printed in the newspaper on 19 February 1906. He reassured the reporter that the deaths were not connected to plague; one person had died from convulsions while the other had died from cervical cellulitis.

In his opinion, typhoid was considered to be a greater problem as Geraldton was not only dealing with its own cases but was also receiving cases from the goldfields. Nevertheless, Dr Hungerford stated that, “The public may rest well assured that when Geraldton is visited by plague they will at once know of it…“

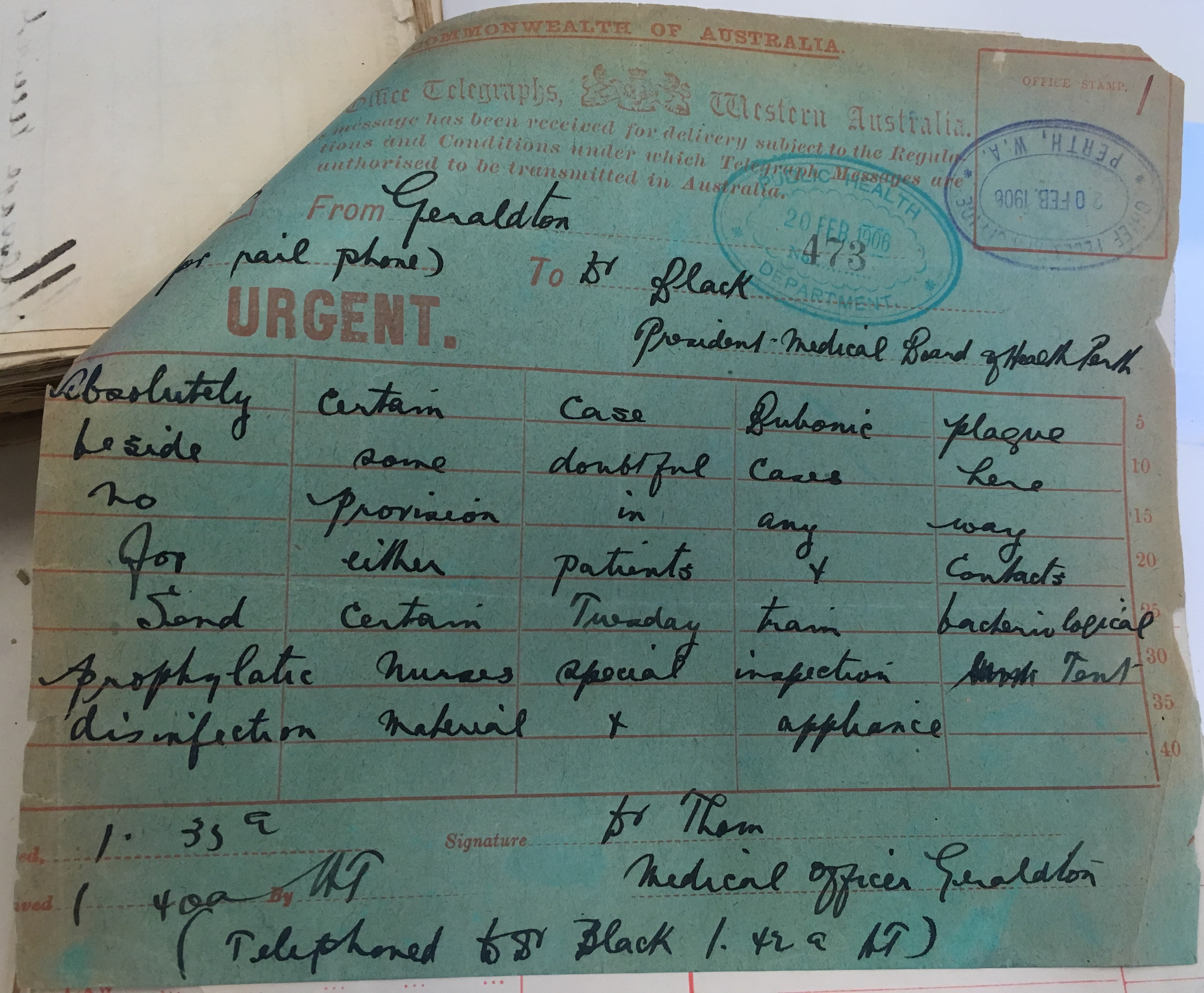

Despite Dr Hungerford’s assurances, on the following day it was reported that Dr Alexander Thom had sent an urgent telegram at 1:30 am to Dr Ernest Black, President of the Central Board of Health in Perth. He declared that bubonic plague in Geraldton was “absolutely certain“. As there was no provision in the town for patients he requested that a “bacteriological [expert], prophylactic, nurses, special inspector, tent, disinfecting material and appliances” be sent up urgently via the next train.

Several hours later Dr Black telegraphed back. It was “absolutely impossible” to send everything on that morning’s train but he promised that he would “arrange everything for next train…” In the meantime he recommended that they take action to isolate the premises and capture rats for examination.

The outbreak had occurred “in quick succession” at the boarding house (the home of the Kruger family) located behind Messrs. Gray & Co.’s shop on Marine Terrace as well as in the shop itself. There were three definite cases of bubonic plague: 22 year old Lily Getty (servant to Mrs Kruger), eight year old Marjory Bennett (Mrs Kruger’s daughter) and 58 year old Charles Gray (the owner).

The revelation caused people to question the aforementioned deaths. John Butcher was well on 20 January 1906 and competed in a cricket match that day. Symptoms showed on the 21st and on the 24th he passed away at age 34.

Ernest Cream was 14 years old and worked at Messrs. Gray & Co.’s shop as a messenger boy. He too was in good health before suddenly falling ill on 15 February. He never recovered and three days later he passed away.

The first priority of Geraldton’s Local Board of Health was to warn the public. By 4 am on 20 February all the business people located on Marine Terrace received a circular advising that there was an outbreak of bubonic plague. It requested that they use “all possible means” to kill the rats on their premises as well as remove all rubbish. As an extra incentive, the Geraldton Council offered a six pence reward for every rat destroyed.

Following Dr Black’s advice, at 8 am the premises of Messrs. Gray & Co. was quarantined. Anyone who was inside was forbidden to leave. Yellow notices were then placed around the building warning that it was plague infested.

Special constables were sworn in and placed on quarantine duty at the property. One was stationed by the front door and another stationed at the back. Along with preventing anyone from leaving the premises, they also warned pedestrians from going within 20 feet of the building line, a task that was apparently never ending.

Complaints were also made to the effect that street pedestrians frequently stopped on the footpath and leaned over the gate to Gray’s yard conversing with contacts.

Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919); 23 February 1906; Page 3.

A decision was made to set aside several areas to treat patients. Anyone who was in an infected area (referred to as contacts) was to be sent to the Quarantine Station near Point Moore. Those who were diagnosed with bubonic plague were to be placed in a specially constructed tent hospital on the Northern Cricketing Association’s cricket ground.

Having taken necessary action, the doctors and the Local Board of Health in Geraldton waited for their requests to be answered by the Central Board of Health. In the afternoon they received a telegram advising that Dr George Blackburne (the bacteriological expert) and Inspector Stevens would leave Perth on the following day via the morning train.

Telegrams and urgent requests (especially for nurses) continued. They remained unanswered. Clearly frustrated, Dr Thom sent another message just after 5:30 am on 21 February. He declared that Geraldton was “reeking with plague” and asked Dr Black what exactly he was doing to help them. When he eventually received a reply it was to state that he had not provided enough detail and that no action would be taken until word was received from Dr Blackburne and Inspector Stevens.

Geraldton meanwhile was in a state of panic. Residents approached the Geraldton Express to air their opinion that the Mayor should hold a public meeting for the express purpose of telling them all that he knew. They also wanted an answer to an important question: why had it taken so long to diagnose the illness as bubonic plague.

Those who had the option to leave began packing their bags. Hundreds of people from the Murchison goldfields (including a group of children from the Fresh Air League) were in Geraldton enjoying a summer holiday. Upon hearing about the outbreak they immediately cut it short and returned home.

The utmost uneasiness prevails among the residents of Geraldton, and a large number of visitors from the fields and elsewhere have left the town. The children from the Murchison, who have been here for a change of air, returned this morning.

Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919); 21 February 1906; Page 2; Bubonic Plague in Geraldton

Adding to the fear, in the afternoon of the 21st it was confirmed that 22 year old Thomas Allen (an employee of baker, John Cantelo) was diagnosed with bubonic plague. Thomas remained in his home on Marine Terrace (opposite Messrs. Gray & Co.) and both his home and the bakery were quarantined. While it was reported in the press as being the fourth case in town, it was in fact the fifth.

Donald Hume was left out of early newspaper reports and even official documents. He too was 22 years old and had arrived in Geraldton on 8 February after having left New South Wales to join his family. The first symptoms of the disease showed up on the 18th but weren’t obvious enough to warrant concern. Thus, he wasn’t confirmed as having bubonic plague until much later.

Initially the four patients (not including Donald) were reported as having “mild attacks” and while there were moments where their conditions improved, over time they worsened considerably. Charles Gray was one of the worst and such was the despair for his health that the local authorities began constructing a funeral pyre in the cemetery before he had even passed away. Not everyone agreed with taking such preparatory action.

It seems nothing less than a supremely callous act to prepare beforehand the revolting paraphernalia incident to such a shocking death, hours before a corpse is available; and, further, to assume, offhand, long before dissolution, that hope is dead, medical skill a mockery, and Heaven itself powerless to interfere, even at the eleventh hour, between the bubonic fiend and his prey.

Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919); 2 March 1906; Page 2; Capricious Carpings

At 1:15 am on Thursday, 22 February Dr Blackburne and Inspector Stevens finally arrived at Geraldton Train Station. They were met by two local Councillors and the Town Clerk. It was arranged that Dr Blackburne would see Dr Thom at 8:30 that morning. Inspector Stevens would carry out a preliminary examination of the plague premises between 6 am and 8 am and then meet with the Local Board of Health at 8:30 am.

When Inspector Stevens examined the premises he found all the patients within their homes. Lily Getty and Marjory Bennett were in separate rooms upstairs in the boarding house and were being cared for by Mr and Mrs Kruger, both of whom had no nursing experience. Charles Gray was in a room upstairs above his shop. He was being cared for by his manager, William Moore, who also had no experience. Thomas Allen was at home and had no one to attend to him. He was eventually moved to a shed on Gray’s property and Charles Fairbeard (who had experience as a nursing orderly in India) was employed to attend to them both.

As part of his duties, Inspector Stevens also looked into the possibility of relocating the patients. He found that the tent hospital was still in the process of being organised and there were no other suitable premises in town to use as a temporary hospital. With the patients far too sick to be moved, a decision was made to keep them where they were. The original plan for the contacts however went ahead. Repairs had been made to the Quarantine Station and, upon completion, all the contacts were removed from their homes and isolated at Point Moore.

Telegraphing to the Central Board of Health on the morning of his arrival, Inspector Stevens ended with a rather grim assessment of the situation.

Gray’s case serious. Dr Blackburne not yet completed diagnosis, will post full particulars tonight. Nurses unobtainable, temporary hospital accommodation, unprocurable, quarantine premises unsuitable for patients.

Central Board of Health; S268 – Files – General; AU WA S268- cons1003; 1906/0473A; Geraldton – plague.

In a letter written on the same day he stated:

There is no mistake about the intensity of the scare…

Central Board of Health; S268 – Files – General; AU WA S268- cons1003; 1906/0473A; Geraldton – plague.

While earlier telegrams sent by Geraldton’s Local Board of Health to Dr Black were deemed “hysterical” and lacking in detail, those sent by Inspector Stevens were immediately believed. The words punctured through Dr Black’s bias and the enormity of the situation finally sunk in. He took decisive action and hired Nurses Kenny and Lawrence who were sent on the express train to Geraldton. He also sent two serum syringes and ordered a supply of Yersin’s Serum (used to treat bubonic plague) from Brisbane. It was all a little too late. A writer for the Geraldton Express was understandably angry at both Dr Black’s response (or lack thereof) and the fact that the Local Board had to wait for instructions from Perth.

The arrival of Dr Blackburne sadly did nothing to help those who were already sick. At about 9:30 pm on the 22nd Marjory Bennett passed away. Preventing the spread of the disease was high priority. Her body was removed from the premises at midnight and taken to the Roman Catholic section of Geraldton’s new cemetery. Using york gum and kerosene, she was cremated at about 2:30 am on the 23rd. It was noted in the Geraldton Express to have been “the first, though alas, not the last, cremation in Geraldton“.

Not long after Marjory’s cremation, Charles Gray passed away at 3 am. As he was in a room that was not easily accessible, his body was placed in a coffin and the old tackle and pulley system located outside his shop (once used to haul produce) was utilised to remove him from the premises.

I never saw the door open, nor the tackle used until I was about 20, when I worked nearby in the stationers shop. One day I saw the door open, and gazing horror-stricken, a coffin lowered down. The last time the tackle was used was to bring down Henry [Charles] Gray when he died of bubonic plague.

Memories of Champion Bay or Old Geraldton; Constance Norris; 1950; Page 9.

Despite the deaths of two of the four patients, plans continued with the erection of the tent hospital on the cricket ground. The nurses from Perth also arrived at 9 am on 23 February and they started work that evening.

To help protect the rest of the town, Dr Blackburne set himself up at the Geraldton Council Chambers and twice daily inoculated residents with prophylactic serum. He took special care to inoculate contacts and people who were living or working on the ocean side of Marine Terrace, which he considered to be the “infected or dangerous” area. He also distributed notices to residents advising that they could voluntarily receive the injection. Eager to take any possible precaution, people anxiously besieged the Chambers and men had to be positioned by the doors to “check the rush of persons desirous of being inoculated.” In two days Dr Blackburne and Dr Thom inoculated 555 people. That figure would later rise to 1,500 people – half the town’s population.

Valerie Eaton was a child at the time and in 1981 she recalled how children of all ages (every class at her school) went down to the Chambers in batches of 20 to receive the inoculation.

When I was at school here, the bubonic plague, and we all…the different classes, when it reached plague proportion, every class had to go down to the Council Chambers to have this needle…

Transcript of the interview with Valerie Cook [sound recording]; Interviewed by Ronda Jamieson; 1981; Call Number: OH433.

The afternoon of the 23rd saw some positive news when the Central Board of Health gave the all clear for the Local Board to release the contacts quarantined at Point Moore. Any hope of the disease abating was later abandoned. 29 year old Walter Bradley was working as a baker’s carter for John Cantelo when he developed a “sudden severe illness“. His home on Augustus Street was quarantined and he remained there to be cared for by his wife and the nurses. After observation Dr Blackburne diagnosed him with septicemic plague.

Two days later Lily Getty and Thomas Allen succumbed to the disease. Thomas died at about 12 am on the 25th and Lily died an hour afterwards. Their bodies were removed from the property mid-morning and were cremated in the cemetery at around the same time.

If we saw a piled lorry of wood with a case of kerosene on top come out of the council yard we knew another patient had died.

Memories of Champion Bay or Old Geraldton; Constance Norris; 1950; Page 47.

From the moment he arrived Inspector Stevens took on the task of cleaning and disinfecting the premises where plague had occurred. He began with Cantelo’s bakery (which was later condemned) and after the deaths of Thomas and Lily, he moved on to Gray’s buildings. Every room and wall was thoroughly cleaned from top to bottom. The shop proved to be the most difficult due to all the products on display. Each item was nevertheless wiped over with a cloth soaked in disinfectant.

Every household was further encouraged to do their own cleaning and disinfecting. The Local Board of Health received a supply of chloride of lime from the Central Board and they offered quantities of the disinfectant free of charge to people who wished to use it.

By the 26 February Donald Hume had been sick for eight days and had only just started to show obvious symptoms of bubonic plague. When Dr Blackburne visited him it was much too late. Donald died at his home on Fitzgerald Street at 1:30 am. His remains were cremated an hour later.

The condition was not typical and the case did not show suspicious symptoms till he had been ill 8 days so that it was not till then that he came under my observation (26.2) and he died the same day.

Central Board of Health; S268 – Files – General; AU WA S268- cons1003; 1906/0473A; Geraldton – plague.

Walter Bradley was the only surviving plague patient. Over the course of a week his condition worsened and improved several times. Unlike the others, he had professional care for the duration of his illness which meant there was a higher chance of recovery.

In early March signs were positive and he was noted as looking cheerful and well and declaring, “plague isn’t going to kill him.” Hopes that he would recover were shattered at 4:30 am on 5 March. Walter’s death was the sixth official death from plague and the Geraldton Express reported somberly that the town held “the lamentable record of the whole world, as regards plague – 100 per cent, of deaths.“

To add to the depressing news, another diagnosis was confirmed. 53 year old Elizabeth Connery was the wife of one of the special constables who was employed on quarantine duty. Due to her husband’s proximity to the disease, she was inoculated on 26 February. While she still caught bubonic plague, it may have been the serum which resulted in the illness only being considered mild. She was the first patient to be removed to the tent hospital on the cricket ground.

By 8 March it was noted that the conditions in relation to the plague outbreak in Geraldton had “changed for the better.” Elizabeth’s health had greatly improved and there was no fear that she would succumb to the illness. Any contacts who were quarantined were released and the special constables were officially discharged from their duties. In Dr Blackburne’s opinion the town was, “…freed from the presence of the disease.“

As hope grew, thoughts of prevention were at the forefront of people’s minds. The Local Board of Health was hard at work and they put in place new measures to deal with sanitary conditions in town. From that point on there would be:

- a bi-weekly rubbish service.

- the provision of standard rubbish bins.

- regular removal of house-slops from hotels, restaurants and noxious trade premises, and

- a systematic supervision of the whole health area with regular reports from inspectors.

Geraldton once made clean, should always remain so, and become an attractive marine resort.

Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919); 9 March 1906; Page 2; Bubonic Plague

Although the town was believed to be free of plague, one more case was to arise. Mrs Ellen Morris (aged 27) was diagnosed on 10 March and was removed to the tent hospital that night. She had not been inoculated and though the illness was severe, Dr Blackburne was confident she would make a full recovery.

Elizabeth and Ellen were the last two people diagnosed with bubonic plague and, by mid-March, both women had recovered. The plague scare in Geraldton had finally ended.

While I’m sure there was a palpable sense of relief at being given the all-clear, the aftermath of the bubonic plague continued to be felt in other areas. Businesses had stagnated and tradespeople were suffering because of it. Hotels had a high vacancy rate and many bedrooms were shut up and locked. No one was eating meals at restaurants and the proprietors had noticed the obvious reduction in patrons. The whole town had become “partially paralysed“. The only thing that was noted to have seen an increase in activity was the amount of people making their Wills.

School attendance was also affected. Rather than sending their children to school and possibly risking exposure to the disease, parents decided to keep them home. The State School recorded a 33% drop in attendance.

Dr Blackburne (who was praised for his tireless work) returned to Perth on 23 March 1906, having spent over a month in Geraldton. At around the same time he wrote his report. In his opinion the outbreak started in the buildings belonging to Messrs. Gray & Co as well as in John Cantelo’s bakery. He could only speculate as to where the disease had originally come from.

It is of course impossible to say where the infection in this town came from originally, though most likely in some goods or unintentionally imported rats from Fremantle where the infection evidently constantly exists though only becoming obvious at intervals.

Central Board of Health; S268 – Files – General; AU WA S268- cons1003; 1906/0473A; Geraldton – plague.

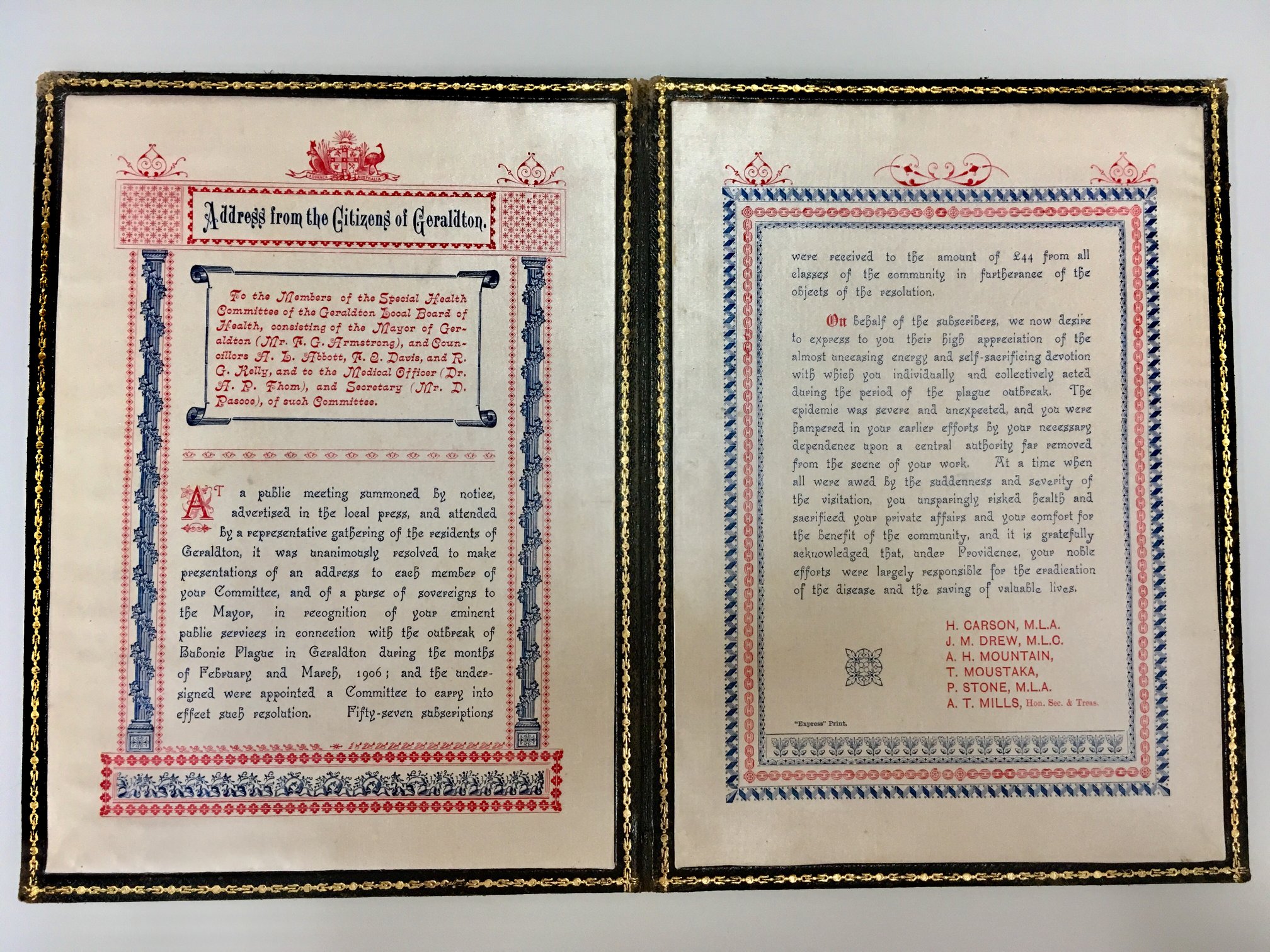

As the months went by relief gave way to indignation. On 23 June 1906 an illuminated address was presented to the Local Board of Health thanking them for all that they did during the outbreak. During the presentation, criticism was levelled at the Central Board of Health and in particular, Dr Black.

It was regrettable that, when the local board had taken the prompt step to wire to the Central Board at midnight, asking for the necessary requirements to cope with the disease, the Central Board did not respond to the call for assistance.

Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919); 25 June 1906; Page 3; The Late Plague.

Four days later the Legislative Council sat in Parliament and John Drew added his voice to the criticism. He stated that he was going to move for the appointment of a Select Committee to look into the Central Board’s conduct. He believed the patients had died from neglect and, due to the Board’s inaction, had “…practically rotted to death.” That move was eventually made in sittings held on 8 August and was carried.

The inquiry was conducted and the report was presented before the Legislative Council on 25 September 1906. The first finding of the report was: “That the Central Board of Health failed to act with that promptitude which might have been reasonably expected when the Geraldton Local Board of Health reported the outbreak of plague, and sought succour.“

It was a bittersweet finding. The Local Board received vindication that the Central Board had failed to act in a prompt manner, however, by the time the report was presented, Dr Black had already been removed from his position and faced no other consequences.

No great change arose from the report itself but there is no doubt that the arrival of the bubonic plague in Geraldton played its own part in changing the town. Ten people contracted the disease; eight people died. The mortality rate was an extraordinarily high 80% and, as one newspaper noted, “Geraldton has had to bear the brunt of the storm.” In such a small town, when someone was sure to have known someone else affected, it was devastating.

The return to “normality” was slow. By October 1906 approximately 400 people who had left during the outbreak returned; an estimated 14% increase that only continued to rise as time went on and fear subsided.

In early 1907 nine year old Gladys Baston arrived in “very, very quiet” Geraldton with her family. They moved into an old two story house and opposite them were a row of shops, still shut up and abandoned because of the plague. She reflected on how it had affected the town in an interview conducted in 1977.

…people were scared you see. They had been closed because of the plague. They had left. Shut up. There was quite a scare for a while. There was one very big shop there it belonged to Mr Gray, Gray’s Store, and Mr Gray died of the plague at the store and I remember that was shut up for a quite awhile.

Interview with Gladys Griffin [sound recording]; Interviewed by Chris Jeffery; 1977; Call Number: OH200. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia.

Perhaps most importantly, the way the Local Board approached future health issues changed and became more definitive. Almost a year after the Geraldton plague, two vessels (originally from plague-stricken Sydney) arrived and were immediately ordered to “stand off“. Only upon inspection and receiving a tick of approval from Dr Hungerford were they permitted to enter the port. That action was taken independent of the Central Board of Health. Geraldton authorities had learnt a harsh lesson from that of 1906 and were no longer prepared to put the town or its people at risk again.

Sources:

- Courtesy of the State Records Office of Western Australia (AU WA A 34 Central Board of Health; S268 – Files – General; AU WA S268- cons1003; 1906/0473A; Geraldton – plague).

- Interview with Valerie Cook [sound recording]; Interviewed by Ronda Jamieson; 1981; Call Number: OH433. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia.

- Interview with Gladys Griffin [sound recording]; Interviewed by Chris Jeffery; 1977; Call Number: OH200. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia.

- Department of Lands & Surveys; Townsite Plans; Item 0666 – Geraldton Sheet 6 [Tally No. 504269]; AU WA S2168- cons5698 0666.

Courtesy of the State Records Office of Western Australia. - 1906 ‘Advertising’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 19 February, p. 3. , viewed 06 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210728925

- 1906 ‘A SCARE AT GERALDTON.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 20 February, p. 3. (THIRD EDITION), viewed 06 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article82678754

- 1906 ‘LATER NEWS.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 20 February, p. 3. (THIRD EDITION), viewed 06 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article82678753

- Views of Geraldton, West Australia, 1893; Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia; Call Number: 2949B/2.

- Memories of Champion Bay or Old Geraldton; Constance Norris; 1950; Pages 9 and 47. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia.

- Public Health and Sanitation, Geraldton 1906: The Bubonic Plague; Philomena Wendt; 1970s; Call Number: PR8679/GER-HIS/11 – 0/s. Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia.

- 1906 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE IN GERALDTON.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 21 February, p. 2. , viewed 07 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210725762

- The State Records Offuce of Western Australia; Freemantle Outports Inwards Jul 1902 – 1915; Accession: 457; Item: 29; Roll: 170. Accessed via Ancestry.

- 1906 ‘DR. BLACK’S CALLOUSNESS.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 23 February, p. 3. , viewed 17 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210727055

- 1906 ‘CAPRICIOUS CARPINGS’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 23 February, p. 3. , viewed 19 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210727078

- 1906 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 23 February, p. 5. , viewed 24 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25633128

- 1906 ‘CALLOCUS CONDUCT OF THE CENTRAL BOARD OF HEALTH.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 23 February, p. 2. , viewed 24 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210727042

- 1906 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 24 February, p. 11. , viewed 27 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25633255

- 1906 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 26 February, p. 5. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25633370

- 1906 ‘LOCAL BOARD OF HEALTH MEETING.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 23 February, p. 3. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210727070

- 1906 ‘PLAGUE ITEMS.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 26 February, p. 3. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210727193

- 1906 ‘PLAGUE ITEMS.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 28 February, p. 3. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210732115

- 1906 ‘THE PLAGUE OUTBREAK.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 1 March, p. 5. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25633567

- 1906 ‘PLAGUE ITEMS.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 5 March, p. 3. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210726147

- 1906 ‘The Plague Outbreak.’, The Murchison Times and Day Dawn Gazette (Cue, WA : 1894 – 1925), 6 March, p. 2. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article233409253

- 1906 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 6 March, p. 5. , viewed 31 Jan 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25633967

- 1906 ‘THE PLAGUE OUTBREAK.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 9 March, p. 5. , viewed 07 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25634244

- 1906 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 9 March, p. 2. , viewed 07 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210728298

- 1906 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 13 March, p. 9. , viewed 07 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25634566

- 1906 ‘LOCAL AND GENERAL’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 23 March, p. 2. , viewed 07 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210731779

- 1906 ‘CAPRICIOUS CARPINGS’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 19 March, p. 3. , viewed 07 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210734418

- 1906 ‘LOCAL AND GENERAL.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 19 March, p. 2. , viewed 07 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210734431

- 1906 ‘LOCAL AND GENERAL.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 21 March, p. 2. , viewed 07 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210731430

- 1906 ‘The Late Plague.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 25 June, p. 3. , viewed 14 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210727753

- 1906 ‘NEWS AND NOTES.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 28 June, p. 6. , viewed 14 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25643214

- 1906 ‘PLAGUE AT GERALDTON.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 26 September, p. 2. , viewed 14 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25689485

- 1906 ‘Local News.’, Geraldton Guardian (WA : 1906 – 1928), 9 October, p. 4. , viewed 15 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66223347

- 1906 ‘No Title’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 7 March, p. 6. , viewed 17 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25634110

- 1907 ‘BUBONIC PLAGUE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 6 February, p. 7. , viewed 17 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25695606

- Records, 1906-1908 [manuscript]; Geraldton (W.A.) Council; Call Number: ACC 2701A; Courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia.

- 1906 ‘SELECT COMMITTEE ON BUBONIC PLAGUE AT GERALDTON.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 3 October, p. 4. , viewed 21 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210729218

- 1906 ‘SELECT COMMITTEE ON BUBONIC PLAGUE AT GERALDTON.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 5 October, p. 4. , viewed 20 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210729953

- 1906 ‘SPRAINS AND BRUISES.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 24 October, p. 4. , viewed 21 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210730552

- 1906 ‘SELECT COMMITTEE ON BUBONIC PLAGUE AT GERALDTON.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 24 October, p. 4. , viewed 21 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210730558

- 1906 ‘SELECT COMMTEEIT ON BUBONIC PLAQUE AT GERALDTON.’, Geraldton Express (WA : 1906 – 1919), 26 October, p. 4. , viewed 21 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210726665

I really enjoyed reading this very well researched story. Something I didn’t know about before. I can imagine how scared the townsfolk would be and how upset later when they realized their friends in the community had died due to lack of immediate response. Well done.

LikeLike

Thank you Flissie. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2019/03/friday-fossicking-1st-march-2019.html

Thanks, Chris

What a terrifying time… one I hadn’t heard about before either..

LikeLike

Thanks Chris!

LikeLiked by 1 person