At 12:40 am on 1 December 1928, a man aged in his 20s was found lying unconscious on a street in Perth. He had severe injuries to his head and was taken to Perth Hospital for treatment. Several days later a trepanning operation was performed and, while it was successful, it may have caused him to develop encephalitis. When the man eventually regained consciousness, he had lost all knowledge of his identity.

At 12:40 am on 1 December 1928, a man aged in his 20s was found lying unconscious on a street in Perth. He had severe injuries to his head and was taken to Perth Hospital for treatment. Several days later a trepanning operation was performed and, while it was successful, it may have caused him to develop encephalitis. When the man eventually regained consciousness, he had lost all knowledge of his identity.

The operation, however, though it restored Brown to life, robbed him of some portion of his mental faculties and, from that day, he has been unable to remember any incident which took place before the operation. His life, up to that date, has been a blank to him ever since.

At the time of his admittance to hospital his address was recorded as the Horseshoe Coffee Palace in Perth. Also provided was the name of a friend who lived in Subiaco. Despite police efforts to locate the person, no one by that name was found. The man had no other relatives or friends and he remained in hospital, unidentified, for nearly a year. He was eventually dubbed, William Brown.

For months both police and hospital staff tried to ascertain who William was by following what little clues they had. He had arrived wearing a “good, neat suit” and a new hat however there was nothing on the labels nor anything in the pockets to help identify him. Scars on his left arm and leg were thought to look like gunshot wounds, though William had no memory of having ever been shot.

While recovering from the effects of anesthetic used during his operation, William was said to have mentioned the cities San Francisco and New York as well as other American ports. Such talk soon resulted in the theory that he may have been an American sailor.

He was described as northern European in appearance and spoke English perfectly without an accent. He could also speak German, Italian and French. It was presumed that he was from another country and a request was sent to the Commonwealth authorities asking that he be repatriated. Of course, without knowledge of where he came from, such a request could not be carried out.

By November 1929 William’s story reached the ‘Mirror’ and they printed his photograph and an accompanying article hoping that publicity would help.

Other newspapers picked up on the story and the joint publicity had the desired effect. Eager Western Australians approached Vernon Eagleton (the secretary of Perth Hospital) offering to help solve the mystery. Many people had relatives or friends overseas whose family member had disappeared and they were hopeful that William might be that person.

A woman who had lived in Kellerberrin came forward and she believed William was the same man who had worked on her farm over a year ago. She recognised him and confirmed that he was generally employed in the area as a farm hand and a rabbit trapper. She then made a statement regarding his name.

Brown, she said, had always been known as William Brown, although he had stated when in Kellerberrin that he possessed another name.

No one knew his real name although he was sometimes known as ‘Yank’ Brown. The statement however throws some doubt on the hospital staff’s choice of name. Did they just happen to pick the same name that he had been known by in Kellerberrin?

Questions were continually put to William. He had no memory of Kellerberrin nor of having worked on a farm. Every now and then he experienced flashes of buildings or scenes but could not name the places. He also had knowledge of shipboard matters, bookkeeping systems and geographical features of England but could not say where this knowledge came from.

The curious case of the man without a name reverberated around the state and captured everyone’s interest. Country newspapers ran with the headline, “Who is William Brown?” He was everyone’s son, everyone’s brother, everyone’s relative; a beacon of hope for people who had lost contact with a loved one long ago and were longing to find them again.

Detective Gavin Findlay was put in charge of the investigation and over time confirmed that William had booked a room at the Horseshoe Coffee Palace on 29 November 1928. He was admitted to hospital two days later, leaving behind a cloakroom ticket as well as a suitcase. The cloakroom ticket was for the Perth Train Station and they were thought to be holding another suitcase and a rug.

Months after his operation, while William was supposed to be at the convalescent home in Cottesloe, he returned to the Horseshoe Coffee Palace and collected the ticket and his case. He then went to the People’s Palace in Pier Street and stayed there for three days.

The proprietress of the Coffee Palace positively identified him as the man she gave the belongings to. William had no memory of having collected the case and the ticket but admitted to staying at the People’s Palace.

At first it was thought strange that he should know where to call for his belongings, but this is explained by the fact that a man who had seen Brown at the coffee palace was an inmate at the hospital for a time. It is thought that this man advised Brown to call for his things and told him where to go.

The ticket and the case disappeared. The other suitcase and the rug at the cloakroom were sold to a man named Kay during a lost property sale in June 1929.

Following up on the theory that William was an American sailor, the American Consul-General in Melbourne was contacted to find out if they were missing a man who had served in the American Navy. The Consul-General, Arthur Garrels, responded via telegram and advised that a second-class fireman named Russel Harvey Brown was missing from the USS cruiser ‘Nevada’. The description of Russel was similar to William. While further inquiries were necessary, the Chief Resident Medical Officer, Dr Anderson, was confident enough to announce, “There is little doubt that Brown is the fireman mentioned in the Consul-General’s telegram.“

Likewise declaring the puzzle solved, the newspaper ‘Mirror’ published a letter from William where he profusely thanked them for all their help.

On the following day, and after having essentially congratulated themselves, the reporters from the ‘Mirror’ were knocked off their pedestal by rival reporters from ‘Truth’. ‘Truth’s’ exclusive instead declared that he was not an American sailor but was an Englishman named Gerald Dawes.

William was identified by Mr J Cooper of Fremantle who had worked with him in the country and immediately recognised him in the photographs. Wanting to help, Cooper visited William in hospital. The subject of his other name was brought up.

One night when we had a bit of a confidential talk together you said to me, “William Brown is not really my name. My real name is Gerald Dawes. I was born in England where my father is connected with Scotland Yard.”

Although the name ‘Gerald’ appears to have been incorrect, by 6 December 1929, William’s identity was (for the second time) confirmed. Reginald Wood came forward to state that William had worked on his farm at Kondinin in 1926 and 1927. He also told authorities that he had been kicked in the shin by a horse and had received treatment at Kondinin Hospital. Sure enough, an inspection of William’s leg revealed that there was a mark on his shin indicative of a previous injury.

Information was requested from Kondinin Hospital which corroborated the story. Coupled with more statements from people who had known him as well as records from the Salvation Army, the truth was finally confirmed. Vernon Eagleton stated, “It has been been established, that the patient known now as William Brown is identical with Harold Dawe, who was a patient in the Kondinin Hospital early in 1927, and that his name is William Leslie Dawe.“

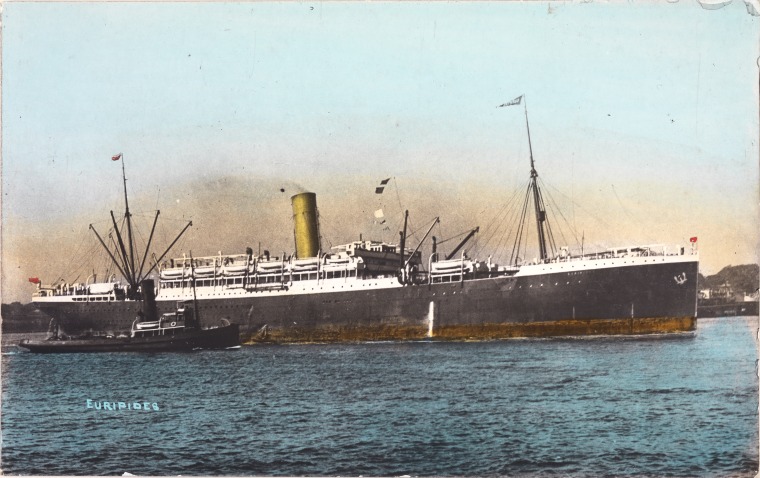

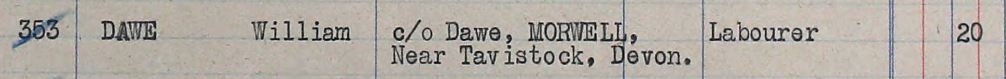

William had arrived in Western Australia on 2 April 1925, on board the ship ‘Euripides’. He was an immigrant under the New Settlers’ League (run by the Salvation Army) and upon arrival was sent to country towns (such as Kellerberrin and Kondinin) to work as a farm labourer. While many other immigrants arrived with their families or siblings, William arrived on his own. His father remained in England but they continued to keep in touch.

While others were thrilled that William was finally identified, William himself was unhappy at the news. He rejected the evidence before him and denied that he was Dawe. Knowing that repatriation was a possibility, he was understandably fearful at being deported to England, to a land he had no memory of and to a father who may not want him.

In mid-December 1929 William was released from Perth Hospital and he obtained a job working for a month for ‘Happy Jack’ at the Hay Street tearooms. It was not a job where he would wait tables or serve people. Such was the public interest in ‘The Man Without a Name’ that William was employed solely to answer questions and sign autographs for curious customers.

In January 1930, as his working  month came to a close, he was approached by the ‘Mirror’ to share his story and they in turn helped publicise that he was looking for work. Nowhere in the article did they mention William Leslie Dawe, they were doggedly of the opinion that he was Russel Harvey Brown.

month came to a close, he was approached by the ‘Mirror’ to share his story and they in turn helped publicise that he was looking for work. Nowhere in the article did they mention William Leslie Dawe, they were doggedly of the opinion that he was Russel Harvey Brown.

This was further pushed throughout the following month when an American naval deserter named J. Mitchell supposedly wrote a letter declaring that he recognised William as his buddy Russel. For whatever reason, it was obvious William preferred Russel’s identity to that of Dawe and he expressed his desire to return to Philadelphia where Russel’s family was said to reside. To help prove his case, he tried to reconnect with J. Mitchell but found that he had disappeared.

Around the same time, contact had been established with William Leslie Dawe’s father in England and he was sent letters and newspaper cuttings relating to William Brown. It had been years since he had seen his son (who was a boy when he left) and there was an element of doubt. He recognised him in one photograph but not in another.

To help, William Dawe Senior provided a great deal of information about his son (who was known as Leslie) which included his date of birth (27 June 1908), the date he left England, the names of his employers in Western Australia (including Reginald Wood), the places of his employment and even the accident with the horse in Kondinin. He further confirmed that they had kept in touch and posted to ‘Truth’ the last letter from his son, which was dated 5 March 1928. In that letter, Leslie finished with a request as to how future letters should be addressed to him.

Well, Dad, next time you write put your letter in an envelope and address it Mr. Bill Dawe, and then put it inside another envelope addressed Mr. Brown, Nalkain, West Australia.

William Senior followed his son’s instructions but the letter was returned to him.

It seemed increasingly likely that William Brown was William Leslie Dawe. Adding to the confusion however was the fact that William Brown appeared to have knowledge of American ports and could speak several languages. William Senior was adamant that his son (aged 16 when he left England) had never been to the United States and could only speak English.

On landing at Albany my son was 16 years and 10 months. And please do not lose sight of the fact that my son has never been in the “States,” and he knows no foreign language whatever: that I swear.

To help clear up the matter William went to the ‘Truth’ office where he was given a piece of paper and instructed to write down what he was told. The words spoken came from part of the letter written by Leslie and the project was carried out with the aim of comparing the handwriting.

The top half was written by Leslie while the bottom half was written by William. In my opinion there were certainly several similarities however there were also many differences. I suppose if they were written by the same hand, it must be acknowledged that one letter was written when the person was well while the other was written when the person was unwell.

For ‘Truth’, the handwriting comparison proved everything and the result left them “no room for doubt.“

The man who wrote the letter to William Dawe, in England, in March 1928, is the same man who wrote, at dictation, in this office yesterday.

Authorities were also convinced. Documents as well as Leslie’s passport were inspected and upon comparison it was found that William and Leslie looked identical. Furthermore, additional information was received from the American Consul-General regarding Russel Harvey Brown. Yes, he had deserted his ship, but he was discovered, court-martialled, found guilty and sentenced to twelve months imprisonment. He was released from prison on 14 March 1927, and while it was possible that he then moved to Western Australia, the timing as well as the witness statements from people who knew William as early as 1926, made it more likely that he did not.

By April 1930, despite having been released and working odd jobs for several months, William wound up back in Perth Hospital suffering from fits. He remained there for a month and in May was presented with a third class single steamship ticket to England. He initially refused to sign the papers but was eventually convinced to do so by Dr Anderson. William complained bitterly about the development.

I am not satisfied that I am Leslie Dawe. Take a look at me, and see if you think I am only 20 years of age, or 21 in June. That’s the age of Leslie Dawe, and if I am not 28 years of age, well I am not born yet. I feel convinced that I am Russell Harvey Brown, of Philadelphia.

Protesting was no use. Determined that William had to leave the country, he was no longer permitted to leave the hospital until the ship that he was to sail on arrived. Meanwhile, another letter from William Senior still did not completely clear up the matter. He expressed himself “in the dark” and “somewhat puzzled” and though he admitted a photo sent to him looked a lot like his son, he was however perplexed by the fact that William had “very thick lips.“

On 26 May 1930 a Government official collected William from Perth Hospital and took him to Victoria Quay in Fremantle. He boarded the S.S. Bendigo “as quiet as a lamb.” The official, ordered to make sure that William left the country, waited on the quay until the ship sailed away.

William arrived in England on 25 June 1930 and was met by a member from the Salvation Army who looked after him until William Senior arrived in London. From London they travelled back home to Bere Alston in Devon.

Two months later William wrote to the ‘Mirror’ updating them that he had been recognised by his father and other relatives and had come around to the fact that he was William Leslie Dawe and not Russel Harvey Brown. He expressed his thanks and gratitude to all who helped him and added an interesting postscript.

Dad said he could not identify the scar on my left arm as it was altered from when he last saw it. When I left England it was a round scar. But the long branch has evidently been done since I’ve been in Aussie, as it has been stitched by a doctor to all appearances, while there has also been another cut on the old scar on the left jaw. Most peculiar, isn’t it?

With the puzzle solved, Western Australians moved on from the story. The only thing connected to William that was left behind was his medical bill. Reported to be £168 ($13,654 today) it was an eye-watering sum that the hospital likely had to absorb. They did however receive a letter of appreciation from William Senior acknowledging the care they gave to William. He also advised that since returning to England there had been no change to his memory.

Mr. Dawe adds that his son has been recognised by all of his relatives, but that he can recognise neither them nor his surroundings.

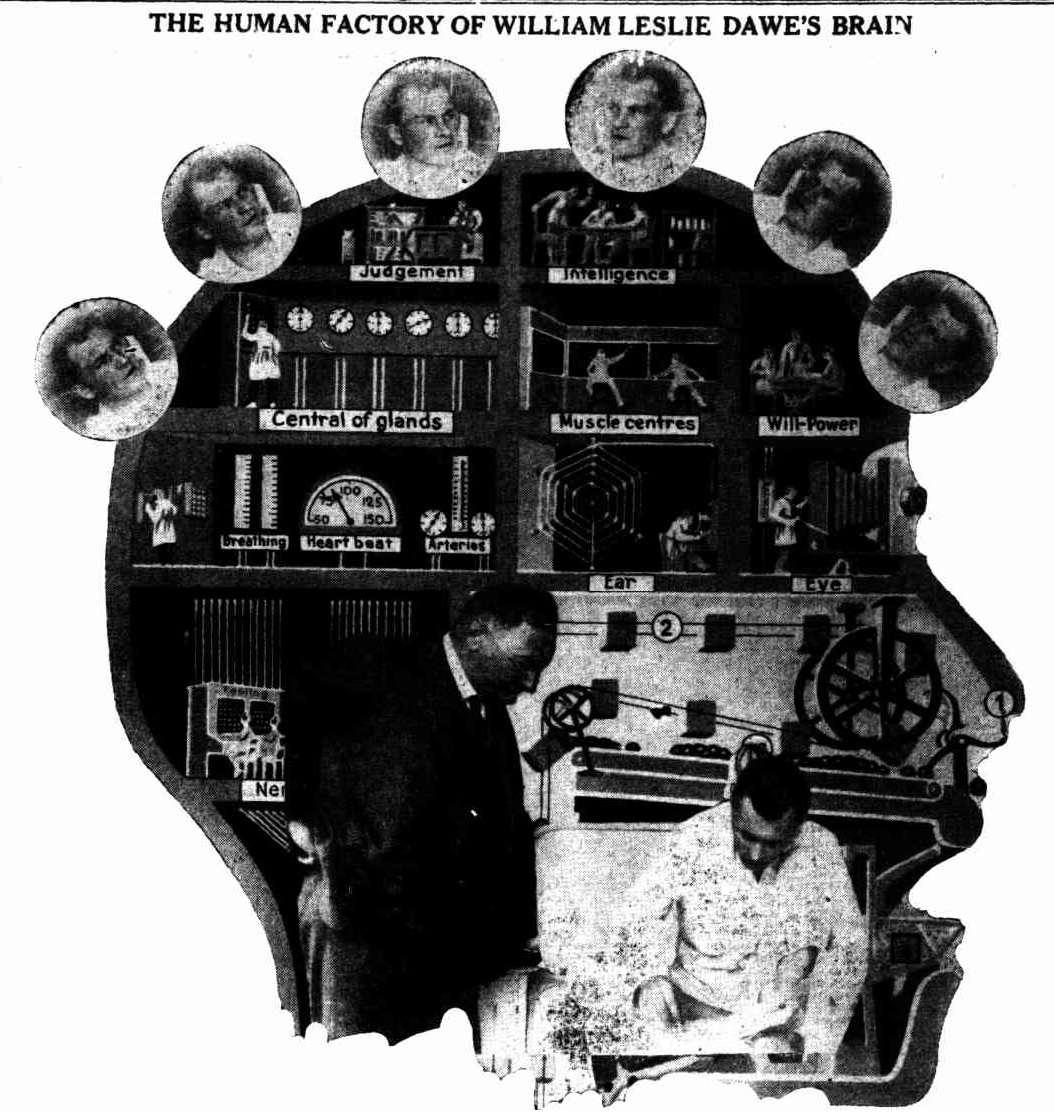

Without medical records and a doctor to look over them, I cannot accurately define what exactly happened to William Brown. In one of their articles ‘Truth’ said that it would be too easy to simply write William off as a “master malingerer and masquerader“. It is a statement I’m inclined to agree with. I’m not a doctor but it certainly seems possible that William’s amnesia and sudden linguistic development could have resulted from the trauma to his head, the trepanning operation, the encephalitis, or, everything combined.

A recent example of a similar case was reported by the SBS in September 2013. After an accident, Melbourne man, Ben McMahon, awoke from a coma speaking only Mandarin. Read the story here:

https://www.sbs.com.au/news/aussie-speaks-fluent-mandarin-after-coma

Questions however will likely remain unanswered. Who was Mr Brown of Nalkain? Why did William tell various people that he had a different name? What happened to the suitcase and ticket? Who was Mr Kay and what did he do with the second suitcase?

At the height of the search William was described by various men from Kellerberrin as a “great yarn teller” who often recounted stories of his travels and his time in the navy. Were these stories true or a work of fiction told to impress people. If they were fiction, did his mind somehow latch on to them during his illness? Could that be why he initially preferred the identity of Russel Harvey Brown?

In the years that followed, William (also known as Leslie) married, had children and lived out the rest of his life in England. It is not known how he fared upon his return and whether any of his old memories came back to him.

The story of the mysterious Mr Brown (who turned out to be Mr Dawe) is fascinating. It reminds us of the frailty of the human brain, the amazing and surprising abilities that can develop out of trauma, and raises the ultimate question, who are we if not for our memories?

Sources:

- 1929 ‘MAN WITHOUT A NAME.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 20 November, p. 19. , viewed 16 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32331416

- 1929 ‘LOSS OF MEMORY CASE’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 21 November, p. 16. , viewed 17 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32331747

- 1929 ‘LOST MEMORY CASE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 23 November, p. 18. , viewed 19 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32332362

- 1929 ‘LOST MEMORY CASE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 25 November, p. 18. , viewed 19 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32332676

- 1929 ‘People of the Week.’, Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), 28 November, p. 4. , viewed 19 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37680734

- 1929 ‘NAMELESS!’, Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 – 1956), 16 November, p. 1. , viewed 20 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76195528

- 1929 ‘MYSTERY MAN THANKS “THE MIRROR”‘, Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 – 1956), 30 November, p. 1. , viewed 20 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76194809

- 1929 ‘UNKNOWN MAN’, Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 – 1956), 30 November, p. 1. , viewed 27 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76194793

- 1929 ‘THE MYSTERY OF WILLIAM BROWN’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 1 December, p. 7. , viewed 20 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210492922

- 1929 ‘LOST MEMORY CASE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 2 December, p. 18. , viewed 20 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32334461

- 1929 ‘LOSS OF MEMORY CASE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 6 December, p. 24. , viewed 20 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32335809

- 1925 ‘NEW SETTLERS.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 28 March, p. 9. (THIRD EDITION), viewed 20 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article84260562

- Photo of the SS Euripides courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia; Call Number: D38b; http://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b3148299_1

- 1929 ‘The Deepening Mystery of William Dawe, Alias Brown’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 8 December, p. 9. , viewed 20 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210493093

- 1930, Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 – 1956), 18 January, p. 1. , viewed 22 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page7427853

- 1930, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 23 February, p. 6. , viewed 22 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page22682689

- 1930 ‘PERTH’S MYSTERY MAN’S IDENTITY NOW SOLVED’, Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 – 1956), 8 February, p. 16. , viewed 22 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76039755

- 1930 ‘NOW WHO IS HE?’, Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 – 1956), 22 February, p. 5. , viewed 04 Oct 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76041584

- 1930 ‘HARD TO CONVINCE’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 4 May, p. 8. , viewed 23 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210496228

- 1930 ‘THE MYSTERY MAN Still in Perth Hospital’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 18 May, p. 1. , viewed 23 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210496426

- The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists.; Class: BT26; Piece: 935; William Dawe.

- 1930 ‘IDENTIFIED AT LAST!’, Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 – 1956), 2 August, p. 1. , viewed 23 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76041854

- 1930 ‘NEWS AND NOTES.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 5 August, p. 8. , viewed 24 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33347032

- 1930 ‘“MYSTERY MAN’S”’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 10 August, p. 5. , viewed 24 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210498409

- 1929 ‘THE HUMAN FACTORY OF WILLIAM LESLIE DAWE’S BRAIN’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 8 December, p. 1. , viewed 24 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210492986

- 1929 ‘MYSTERY MAN GETS A JOB’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 22 December, p. 1. , viewed 24 Sep 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article210493391

Wow – what an interesting intriguing story and researched well. I’d love some of the remaining questions to be answered.

LikeLike

Thank you flissie. 😊 I’d love to know the answers too!

LikeLike

A little unconfirmed research shows that he got in a little trouble with passing a dud cheque in England. If i have the right guy he left his wife and his children and his son was still looking for him.

It would be great it if we could get his death certificate. I think it will show as “death in absentee”

I believe he returned to Australia. This might be just the first part of the mystery.

A story well told Jessica Barratt.

Dawe

Forename(s) of Deceased

William Leslie

Reference Information from GRO Index

1971

Quarter

District Name

Birmingham

Volume Number

9c

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Jon! And great work on the research regarding the cheque. Hopefully the death certificate holds more clues. I’d love to confirm what happened to him. He created a mystery when he was in hospital in Perth and the mystery continues to this day!

LikeLike

I believe I am the great grandson of this man. My grandfather doesn’t remember him as he left when he was a baby and never met him again, but from the research I have carried out, all evidence and pictures show resemblance to my grandfather. I would be interested to know more about the cheque.

I have a copy of his death certificate, and have been in contact with his remarried family.

LikeLike

I believe I am the great grandson of this man. My grandfather doesn’t remember him as he left when he was a baby and never met him again, but from the research I have carried out, all evidence and pictures show resemblance to my grandfather. I would be interested to know more about the cheque.

I have a copy of his death certificate, and have been in contact with his remarried family.

LikeLike

Hello Jon Ambrose. I have lots of information on him and the passing of the cheque. Can you tell me what the cause of death the certificate says. I will send Jessica Barrett my email address if you wish to make contact.

LikeLike

Hi Jon,

With your permission, are you happy for me to share your email with Jon Ambrose?

LikeLike

Becoming more and more interesting

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please pass on my email Jessica.

LikeLike

Was there any update on this? Did he turn out to be your Great Grandfather @Jon?

LikeLike