The following blog post contains descriptions which may be distressing to some people. Readers are advised to proceed with caution.

Note: many different names were used to identify the mine featured in this blog post. For continuity, I have opted to use what appeared to be the most commonly used name, the Rose Pearl.

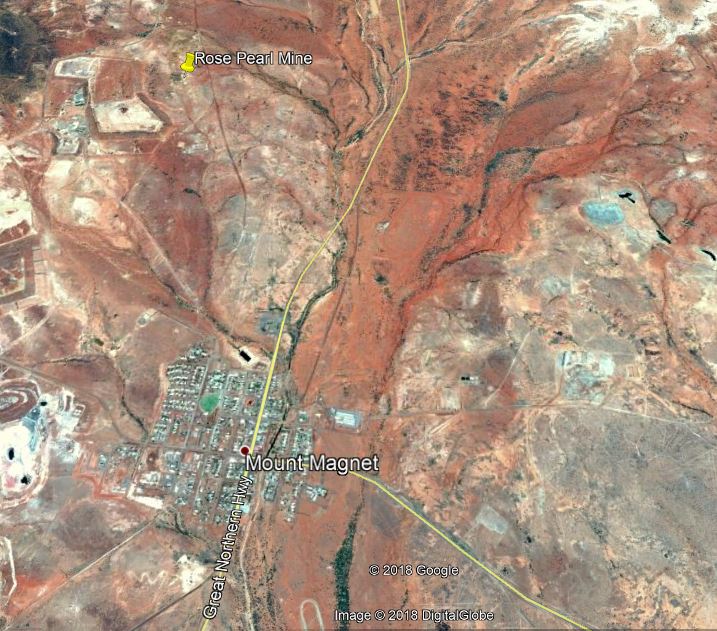

For six months the mine known as the Rose Pearl sat dormant on the outskirts of the town of Mount Magnet. The company that owned it was being restructured and more time was needed to arrange for work to begin again. Until that happened the mine shafts were covered to prevent accidents and the Rose Pearl was essentially abandoned.

John Pringle had been the mining manager before the closure and as time lapsed on the exemption granted to the owners it became apparent that the likelihood of the mine operating again was slim. By mid-November Mr Malcolm Reid was interested in taking over a couple of the leases and lodged an application to do so. Wanting to view the mine for himself, he approached Mr Pringle asking if he would be willing to show him over the lease.

Early in the morning on Sunday, 27 November 1898, Mr Pringle and Mr Reid travelled north from Mount Magnet to the Rose Pearl mine and descended the ladder of the shaft known as ‘Big Ben’. They were about halfway when Mr Reid noticed a terrible smell. It intensified as they continued down the ladder to the bottom of the shaft (110 feet). Finding it overwhelming, Mr Reid lit his pipe.

Mr Pringle was first to reach the ground but said nothing. Mr Reid followed and as he stepped down he trod on something which did not feel like earth. Moving his candle closer to investigate the object, he found to his horror that what he had stepped on was the calf and foot of a person. Their reaction was one of shock. Mr Reid remarked:

There’s no dog or snake about this lot; it’s a man.

Mr Pringle began ascending the ladder and Mr Reid quickly followed, commenting on the fact that the legs had been chopped off. Upon reaching the surface they immediately returned to Mount Magnet and made a report with Corporal George Pilkington who was the police officer in charge of the town.

Corporal Pilkington, accompanied by Constable John Alliss, drove out to the Rose Pearl gold mine to investigate. Both men went down the ladder of the mine shaft, saw the remains and then returned to the surface to begin the process of retrieving them. Constable Alliss went back down into the shaft and, with the help of an Aboriginal tracker, collected eight parts of the legs and arms, put them in a bag and brought them to the surface. He noted that the remains were found scattered on the bottom and looked as if they had been tipped out of a bag from the top of the shaft.

The search continued for the remaining parts of the body and Constable Alliss suggested that they investigate a shaft about 200 metres north-west of their location and only six metres from “one of the busiest tracks in the District.” His proposal stemmed from prior knowledge of the area. He had ridden past the shaft three weeks earlier and had noticed a bad smell which at the time he assumed was an animal. This particular shaft had no ladder in place and thus a windlass and rope was erected and Constable Alliss lowered into the depths. Upon reaching the bottom (60 feet) he came across a chaff bag with something in it weighing about 14lbs. He sent it up to the surface.

The contents of the bag were examined once Constable Alliss had been hauled out of the shaft. By that time it was the early afternoon and Dr John Saunders had arrived to provide his professional medical opinion. Upon opening the bag it was found to contain the head and part of the torso of a person.

All the parts of the body (in various stages of decomposition) were brought together and compared. Due to the deeper mine shaft and the presence of cool air, the limbs were in a better state than the head. The flesh was still attached to the bones and the hands were mummified. In contrast, the head had been thrown down a shorter mine shaft which was much hotter. It had completely decomposed leaving only the skull. It was described in one report as being “…as bare as if scalped or exposed to weather for a long time.” On the left side of the skull was a large hole (three and a half inches long by two and a half inches wide) indicating that the individual had been violently hit over the head.

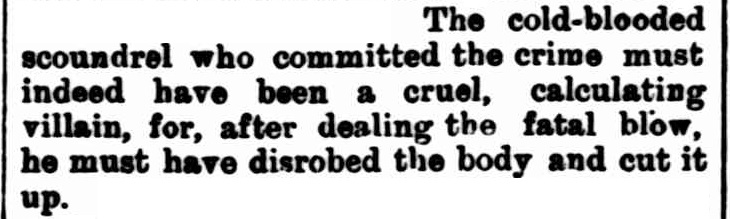

Dr Saunders looked over the remains carefully and made note of the way in which the body had been dismembered. The clothes had been removed and discarded and all the limbs were cut off at the joints using a knife; the legs at the hips and knees and the arms at the shoulders and elbows. The spinal column had also been severed however the perpetrator did not cut through a joint; they had cut straight through the bone of the second dorsal vertebrae.

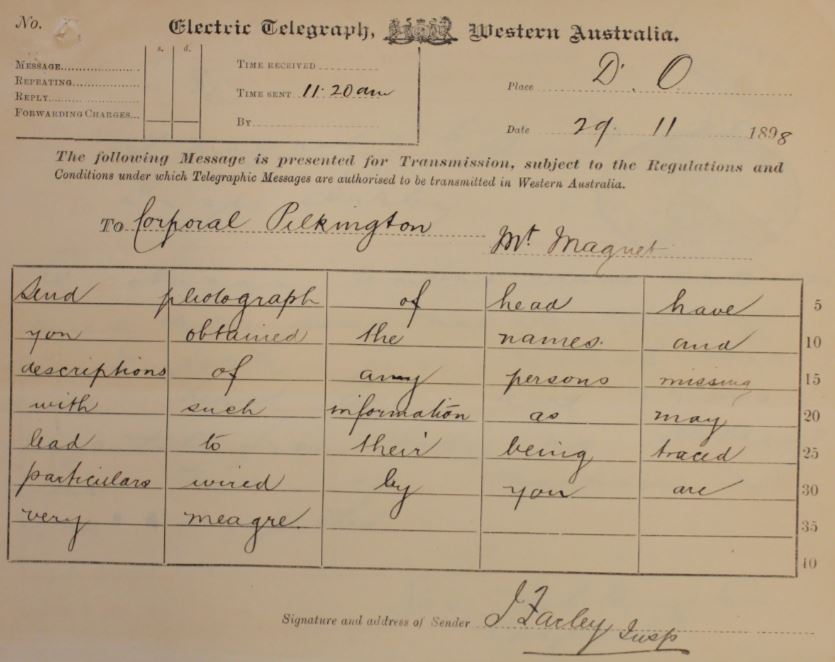

For the rest of the afternoon the police continued searching for the missing portion of the body (the lower part of the torso). Unsuccessful, that evening Corporal Pilkington sent a telegram to his superior, Sub Inspector James Connor at Cue.

It was inevitable in a small town that word would soon spread of the discovery. The Murchison Advocate reported that the news “cast a gloom over the place.” Groups of men huddled together in the streets discussing both the victim and the murderer. They speculated as to the identity of the man who was dismembered so horribly and wondered where the perpetrator was. Was he still among them? Notes and thoughts were compared as they attempted to establish who was missing in the town.

At 7:20am on the following morning (28 November) Sub Inspector Connor took the train from Cue to Mount Magnet. Upon his arrival he went out with Dr Saunders and looked over the remains. An inquest was conducted that day and a jury consisting of Richard Albertson (foreman), John Cleary and Daniel McIntosh were empanelled. Mr Joseph Bryant was the Acting Coroner. After swearing them in, Mr Bryant adjourned the inquest so that he and the jury members could view the remains which had been left lying in the scrub about a kilometre outside of town.

Aged between 40 and 50 years old the man was European, of solid build and about five feet eight inches tall. He had a low, receding forehead and was missing quite a few of his teeth. While his beard and the hair on his head was thought to be reddish brown and greying, the hair on his arms and legs was stated to be black. His hands were small and the fingers long with neatly trimmed fingernails, a sign the police believed indicated that he was not accustomed to manual labour.

It was noted that the head was found wrapped up with a chaff bag as well as with a piece of calico (thought to have come from a tent) which was heavily stained with blood. It was then placed within another chaff bag which was marked on the outside with a W over the letter L in green paint. Police asked carriers and forwarding agents if they recognised the marks however no one was able to help.

Due to the decomposition Dr Saunders was unable to ascertain an exact date of death. He estimated that it may have occurred sometime between three weeks (early November 1898) and two months (September or October 1898) before the remains were found. The cause of death was due to being hit over the head with a blunt object. In the Doctor’s opinion, death was instantaneous.

The inquest resumed later in the day and it was decided that it should be adjourned for eight days in order to provide the police with ample time to try and locate the missing part of the body. The remains were left where they were under surveillance and the police continued searching.

On the same day a telegram was sent to the Commissioner of Police, George Phillips, advising him briefly of what had occurred. The response came from Inspector Joseph Farley of the Detective Office. He initially requested a description of the deceased however as Corporal Pilkington was unable to offer much due to the decomposition of the remains, he wired back on the following day asking for a photograph.

On 29 November 1898 evidence was heard at the inquest relating to the finding of the remains. Along with his description of the discovery, additional information was put forward by Mr Pringle. He stated that in July some canvas had been stolen from the mine site and in mid-October part of a tent was cut and taken away. The rest was stolen several weeks later. He could not say with certainty if the stolen canvas and tent were the same as what was used to wrap around the head.

In early November Mr Pringle noticed that a tool chest left near the Rose Pearl had been opened and a tomahawk and saw (which he was certain were placed on the bottom) were found lying on top. No blood was observed on either of the tools and there was no way of knowing if they were used by the perpetrator.

Finally, he recounted that he had seen a man hanging around the ‘Big Ben’ shaft (where the limbs were found). He was wearing khaki pants, a white shirt and a black vest and walked away quickly as soon as he realised he was being observed. Mr Pringle followed him but the man disappeared. He could not identify him.

Constable Allis gave his evidence relating to the finding of the remains and provided an additional fact; in the same mine shaft as the head was a newspaper fragment from The Morning Herald dated 17 November 1898. It was not stated whether the piece held any meaning in relation to the case. There is the possibility that it pointed to a date in which the remains were disposed of however it could simply have been rubbish.

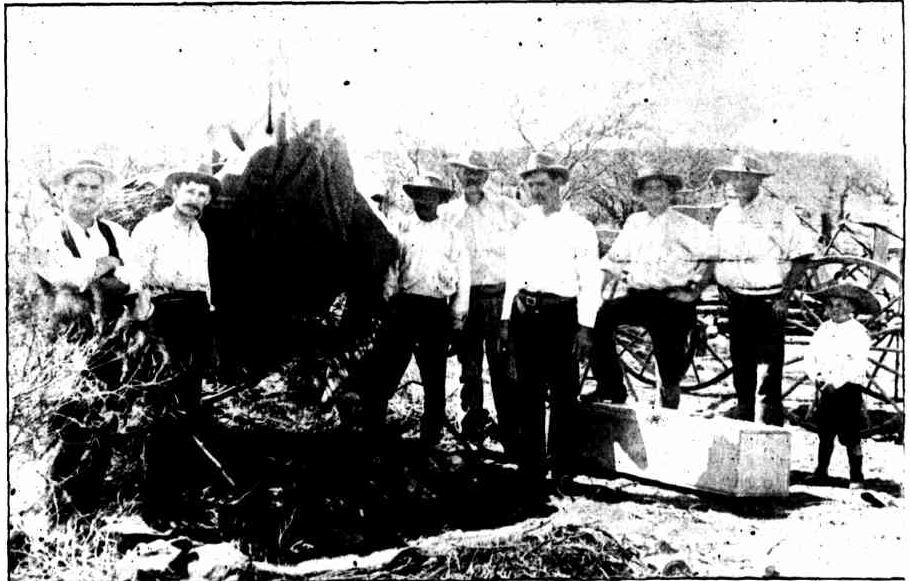

On the same day police also organised the aforementioned photo which was requested by Inspector Farley. Rather than just the one, Mr Hill of White & Wall Bros. took two photos of the search (above) and one of the remains. Parts of the limbs were placed around the skull and torso in an attempt to regain the man’s human condition; forearms and hands at the top and the calves and feet at the bottom. The other portions of the limbs were lined up on either side of the arms. Propped up in the centre was the skull and torso. Devoid of any flesh whatsoever the jaw yawned open in abject horror.

Almost from the very beginning the media reported heavily on the story. The crime and the details of the dismemberment were so shocking that not only did it make the news in Western Australia, it made the news around the entire country. Headlines were printed in large font with the crime often referred to as the ‘Mount Magnet Mystery’. In a rather sensational statement, several papers even likened the murder to those committed by Jack the Ripper.

Almost from the very beginning the media reported heavily on the story. The crime and the details of the dismemberment were so shocking that not only did it make the news in Western Australia, it made the news around the entire country. Headlines were printed in large font with the crime often referred to as the ‘Mount Magnet Mystery’. In a rather sensational statement, several papers even likened the murder to those committed by Jack the Ripper.

Over the next eight days the police (as well as a number of other people) searched diligently for the missing part of the man’s body. Many of the other mine shafts near the Rose Pearl were investigated and, as most did not have ladders, windlasses and ropes were erected. It was often Constable Alliss who was lowered down into the shafts to search for the remains with nothing but a candle. Having to “traverse damp, lonely, reverberating galleries in the depths of the earth” would understandably overexcite the imagination.

The uncanny and weird associations incidental to a search for human remains in old and abandoned works are apt to have a most unsettling effect on the nerves of the searchers.

As well as searching for the missing part of the body, police followed up investigations relating to the identity of the deceased man. If they knew who the man was they would have a better chance of uncovering the perpetrator. They visited all the miners’ camps, mine sites and nearby towns. No one could provide any information that would help them.

Enquiries made at Lennonville, Five Mile and Boogardie made but could not hear of any one missing nor any clue upon which to work.

Men from all around the district travelled to Mount Magnet to view the remains. It would have been understandable if no one was able to confidently state that they recognised the deceased however several thought they did. With a few leads to follow up, Sub Inspector Connor organised for a coffin to be constructed and the remains were brought to the cemetery where they were kept in a building.

Both John Wallgren and Percy Dyer said that the skull resembled the features of their mate, James Peterson, who had left Mount Magnet in August 1898. Peterson (a Swedish man and a miner) was further described as having similar hands and hair colour to the deceased. It was worth following up and a special inquiry notice was printed in the Police Gazette asking for information relating to his whereabouts. A few days later Peterson was found alive and well at Gabanintha.

John Cleary (the aforementioned Juror) advised Sub Inspector Connor that he thought the remains resembled John Quinlan, a man he had known for years and who had not been seen in town for months. Again, Quinlan was traced by the police and was found dry blowing at Horse Shoe mine near Peak Hill.

Several men were known to have worked in the vicinity of the Rose Pearl leases and were interviewed in the hope that they saw something. Having traced John Brockelbank to Yalgoo, he confirmed that he had been in the area with his brother-in-law, Leedham Walker and mate, Robert Wherland. He stated that they noticed a terrible smell coming from the mine shaft and told a Constable about it but could not remember his name. Brockelbank had also reported his bucket and rope stolen on 10 November 1898. Rather than waiting to see if it was found, he left with Walker just over a week later and a week before the remains were found. Perhaps the men, for some reason or another, had become wary of being near the Rose Pearl.

The police were constantly faced with leads which initially seemed promising but were soon resolved or came to nothing. With options dwindling it seemed remarkable that nobody had noticed anything out of the ordinary.

The community is a very small one, and even supposing that the victim was a comparative stranger in the locality, he is sure to have been noticed by someone in the place. It is quite impossible that two men can have arrived at the Magnet without someone being aware of the fact.

All of the circumstances of the case and especially the advanced decomposition of the remains had combined to make, what appeared to be, the perfect crime. There was also the possibility that there were people in Mount Magnet who had noticed something strange but had decided to keep quiet.

On 3 December 1898, Sub Inspector Connor returned to Cue and the next day wrote his report. He noted the extreme difficulty in trying to ascertain who the deceased was and who killed him without the identification of the remains. In his opinion the murder “…must have been committed some distance from where remains were found, and cut up for transport purposes.” Although he had left Mount Magnet the local police continued to make inquiries.

Two days later, the Commissioner of Police sent a telegram to Corporal Pilkington. The tone and language indicated that he was not pleased.

By whose authority were series of sensational photographs taken of remains of man found in mine shafts at Mount Magnet. How came police to allow any person to interfere with remains.

By all appearances the Commissioner had been given notice that the photos (two of the men associated with the search and one of the remains) would be printed in a week’s time in the Western Mail. Corporal Pilkington wired back that the order for the photos had originated with Inspector Farley however Farley denied that what was produced was what he requested. In a memo to the Commmissioner, Inspector Farley later noted that the photographer, Mr Hill, had taken them as a ‘speculation’. Illustrating the level of interest in the story, Mr Hill left Mount Magnet, arrived in Perth and quickly sold them to the newspaper. The photos and their publication in the press was a black mark on the police investigation.

On 6 December 1898 the adjourned inquest was resumed at 10am. The police had not found the missing part of the remains and as there was no other evidence to be heard the jury recorded a verdict of, “A man name unknown came to his death by being murdered by some person or persons name unknown…“

Unwilling to give up, that afternoon Constable Alliss left the station and searched the bush as well as various mine shafts south and east of Mount Magnet. He visited the Primrose and Mayflower Gold Mines and asked the men there if they knew of anyone who was missing. No one knew anything.

Rumours continued to swirl around Mount Magnet and the Murchison district. People began to talk (likely in jest) that the remains belonged to the Member for South Murchsion who had not been seen for a while. This prompted a response from the newspaper that, “Folks shouldn’t try to make out that because a man is politically dead he is extinct altogether.” The residents of Cue were also talking and wondered whether the remains were actually those of a woman. This too was nipped in the bud by reason of the beard and hairy arms.

Others began to lament whether the perpetrator would ever be caught. The vast distances of the outback and the often nomadic ways of the prospectors seemed too great an obstacle for police to overcome. The Murchison Advocate begged the question:

On 8 December 1898 Sub Inspector Connor received notice that he was to be transferred from Cue to Roebourne. No longer in charge of the Murchison District, his position was taken over by Sub Inspector Orme. The change apparently happened at short notice and while no reason behind the action was reported in the newspapers, many assumed it was a promotion. It is nevertheless surprising that an officer familiar with the case and the circumstances was removed so suddenly. Was the Commissioner of Police unhappy with his work on the case? Was it a result of the photographs published in the papers? Or, was it simply standard changes and was a promotion after all?

The police spent the rest of December tying up loose ends. On 13 December 1898 Corporal Pilkington wrote his Supplementary Report relating to the inquiries pursued by the Mount Magnet police. He reiterated the action taken and the lines of inquiry which were investigated. Despite exhaustive searching the police were no closer to finding the answers.

No trace can be found of the missing portion remains and no information can be gained as to the identity of the remains found or any person missing that would lead to tracing the murderer.

While there was a stagnant period where no new clues were obtained, the police were however still working on the case in the background. In the absence of any new information, the media mused, speculated and hoped that the perpetrator would eventually be caught.

The public would like to see the criminal suffer, but at present it looks as though the man has got clean away, and left no clue to his or his victims identity. This is a case in which a Sherlock Holmes is badly wanted, but he does not seem to be obtainable. We hope that the police will not give up their efforts to trace the criminal, and that the latter will eventually be found and made to pay the penalty of his deed.

In late December 1898 the subject of a reward was broached when a wire was received at Cue that the Victorian Government had offered a reward for information relating to the murder of woman. Many people began to question why the Western Australian Government had not yet offered a similar reward for the Mount Magnet murder. The Murchison Advocate, in particular, was scathing in their opinion when they found out that a reward was offered in connection to a robbery at the Post Office.

Without new leads it was inevitable that the initial intense media coverage of the murder would eventually die down. The Mount Magnet police never gave up on the investigation and quietly continued working. As is often the case today, their first major breakthrough came from a member of the public in January 1899.

…I have received information from Henry Baldwin that a young man named John Ward came in to Pierce Miners’ Club at Mt Magnet at 10pm on the 9th instant… Ward commenced talking about the murder.

Sources:

- State Records Office of Western Australia; Western Australian Police Department; Crown Law – remains found in abandoned shaft, Mount Magnet; Reference: AU WA S76- cons430 1902/5032.

- Image of Mount Magnet in 1900 courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia; Call Number: 090659PD.

- 1898 ‘Warden’s Court’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 30 July, p. 2. , viewed 05 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158211014

- 1898 ‘MOUNT MAGNET MYSTERY.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 30 November, p. 4. , viewed 18 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article82399821

- 1898 ‘THE INQUEST.’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 3 December, p. 2. , viewed 18 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158211393

- 1898 ‘A CRUEL MURDER. A DEVILISH DEED.’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 3 December, p. 2. , viewed 20 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158211391

- 1898 ‘MT. MAGNET MASTERY.’, Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 – 1954), 9 December, p. 30. , viewed 25 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33154887

- 1898 ‘THE MAGNET MURDER.’, Murchison Advocate (WA : 1898 – 1912), 3 December, p. 3. , viewed 26 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article213828856

- 1898 ‘THE MOUNT MAGNET MYSTERY.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 29 November, p. 5. , viewed 26 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3221895

- 1898 ‘MYSTERIOUS MURDER.’, The Murchison Times and Day Dawn Gazette (Cue, WA : 1894 – 1925), 29 November, p. 3. , viewed 26 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article233217414

- 1898 ‘General News.’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 3 December, p. 2. , viewed 28 Jan 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158211401

- 1898 ‘General News.’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 10 December, p. 2. , viewed 06 Feb 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158211423

- 1898 ‘General News.’, Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 – 1926), 17 December, p. 2. , viewed 06 Feb 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158211468

- 1898 ‘THE MAGNET HORROR.’, Murchison Advocate (WA : 1898 – 1912), 10 December, p. 2. , viewed 06 Feb 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article213830565

- 1898 ‘THE MAGNET MYSTERY.’, The Murchison Times and Day Dawn Gazette (Cue, WA : 1894 – 1925), 22 December, p. 2. , viewed 07 Feb 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article233218107

- 1898 ‘Local and General.’, Murchison Advocate (WA : 1898 – 1912), 24 December, p. 2. , viewed 15 Feb 2018, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article213832722

Good yarn and well told Jess. Look forward to part II.

LikeLike

Thanks nannajules. Glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Very interesting looking forward to the second part

LikeLike

Thank you Sandra. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Enjoyed the read. But would have thought the missing part of the torso would have been recovered.

LikeLike

It was! But not until many years later. It’ll be mentioned in Part III of the story.

LikeLike