This blog post is a follow up to Death at Lake Austin. You may wish to read Death at Lake Austin first before reading the story of Credgington and Bradbury.

Old Mate! In the gusty old weather,

When our hopes and our troubles were new,

In the years spent in wearing out leather,

I found you unselfish and true –

I have gathered these verses together

For the sake of our friendship and you.To An Old Mate – Henry Lawson

Having a mate on the goldfields may not have been preferred or necessary for some but for others it certainly helped. It meant there was someone there to talk to; to share in the ups and downs and discuss the next move over a cup of billy tea. It meant the jobs of prospecting and transporting equipment as well as the burden of costs were shared. Most importantly, it meant there was someone there to look out for you should anything untoward happen.

Alfred Credgington and Ernest Bradbury’s stories were separate for most of their lives. Both were chasing the golden dream and it was this dream, on the goldfields of Western Australia, that led the pair to meet; their stories converging and remaining joined indefinitely.

Born in 1866 in Cannock in the County of Staffordshire in England, Alfred was Thomas and Ellen Credgington’s fourth child. The first ten years of his life were spent living in England before the family emigrated to New Zealand in 1874. They made their home in Caversham in Dunedin and it was there that we first see a glimpse of Alfred in his youth, winning a school prize for reading in 1877.

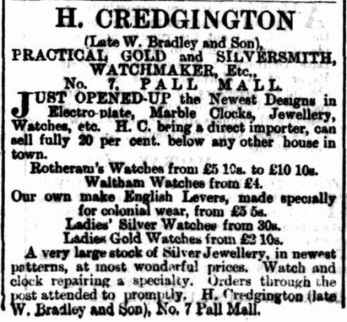

His elder brother, Herbert, was a jeweller and, after initially working in Dunedin, made the move to Victoria in 1887 where he set up his business at No. 7 Pall Mall in Bendigo.

Alfred followed his brother into the jewellery trade and first worked in the profession at Caversham in New Zealand (appearing in the electoral roll for 1890) before following him to Australia several years later. He joined Herbert’s business at Bendigo and was mentioned in the book, ‘Bendigo and Vicinity’ compiled by W. B. Kimberly and published in 1895.

Herbert’s premises were described as a “veritable palace of jewels” and was considered “one of the finest goldsmith’s houses outside of Melbourne.” While the downstairs part of the shop displayed items such as watches, chains and jewels, the upstairs was reserved for the jewellery factory. It was also where Alfred could be found.

Upstairs is the jewellery factory, where Mr. Alfred Credgington, who is a thoroughly practical jeweller and goldsmith, manages. All general repairs are done here, also watch repairing;…

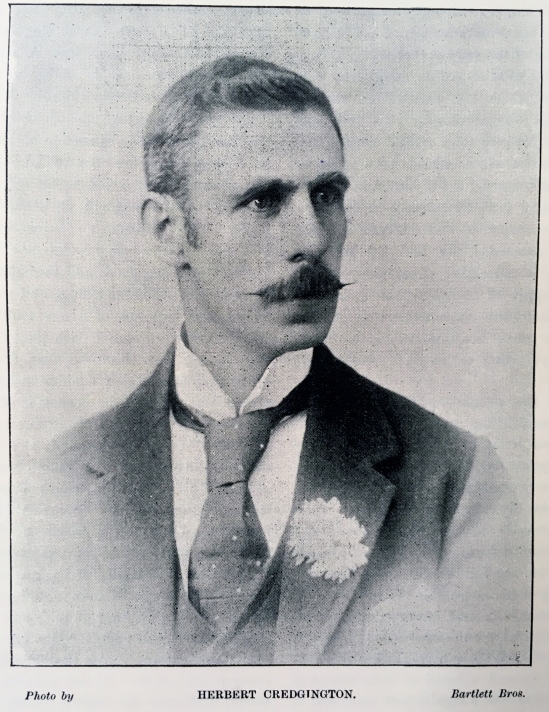

In the middle of the extensive description of Herbert’s life, background, travels and shop is an elegant photo of the man himself. It’s not a photo of Alfred however one can’t help but wonder, in looking upon his brother, whether we are looking upon a similar likeness.

Herbert Credgington was not just a jeweller. He was also a merchant and an astute businessman with experience in the Bendigo gold mines. As the new goldfields gleamed temptingly to the west, Herbert turned his attention towards them.

On 10 July 1896, the steamer Cloncurry arrived in Albany from the eastern states. On board were the Messrs Credgington which, given the pluralised title, indicates that Herbert was not alone when he arrived in Western Australia. Alfred (age 30) was most likely with him.

Throughout the second half of 1896 and some of 1897 they were situated on the goldfields with Herbert responsible for piloting a new syndicate at the Napoleon gold mine near Lake Cowan (north of Norseman).

By March 1897 and in the following months, he began selling up. A bicycle, a hotel on the goldfields, a boarding house and a “handsome six-roomed House” twelve minutes from the Perth Post Office all had to go. He departed Western Australia in January 1898 however Alfred stayed behind.

It appears that Alfred may have been working with Herbert. Herbert was the business side of things while Alfred was more practical and managing onsite. Herbert however struggled to get the syndicates off the ground and Alfred had to fend for himself for a while. On his own in Mt Malcolm, he got into a bit of trouble.

On 28 November 1898, Alfred (age 32) was brought before the Police Court in Mt Malcolm charged with stealing twelve tins of condensed milk, the property of Flannery & Co. (merchants). He pleaded guilty and asked the Resident Magistrate if he could be dealt with under the First Offenders’ Act. His request was granted and Alfred was released on the promise that he would be on good behaviour for one month.

By July 1899 word reached Coolgardie that Herbert had brokered a deal to merge Tindal’s Gold Mine with Golden Dykes Junction and other leases in the Coolgardie area. It was reported on 5 August that Alfred was to be in charge.

Work of a prospecting character is being carried out on Tindal’s under the direction of Mr A. Credgington, who represents the syndicate having an option over the property.

His promotion was short lived. Three days later the Coolgardie Miner backtracked from the above statement.

In connection with the option over Tindal’s, it may be mentioned that Mr J. Scaddan has not relinquished the management of the mine, his position being unaltered.

Indicating that what they had written may have upset Mr Scaddan, they continued to praise his management ability.

Mr Scaddan’s connection with the mine dates back a considerable time, and throughout his career he has proved himself a manager of considerable ability, for much of the success that has attended Tindal’s has been due to his perseverance and good judgment in dealing with this low grade proposition.

Removed from his position, Alfred left Coolgardie and travelled northeast to the town of Boulder where he fell back to his original profession and obtained a job as a jeweller working for Mr James Robertson.

For the next three years Alfred worked without attracting too much attention to himself. Though he remained out of the papers it seems he was battling with a dependence on alcohol.

On 22 February 1902 Alfred was arrested at 3am and was brought to the Boulder Police Station by Police Constables Grieves and Pape. He was known by a shortened version of his name (Fred) and was subsequently recorded in the Occurrence Book as Frederick. This may have stemmed from an assumption on the recorder’s part.

Noted as being age 30 (younger than his actual age of 36) the recorder simply wrote ‘Eurp‘ (European) and ‘Chr‘ (Christian) afterwards. Generally referring to nationality and religious denomination, Alfred may have been elusive with handing over his personal details. This may mean that the Police had no other option than to choose broad categories based on the way he looked. They further specified that he could read and write and that his occupation was a jeweller. He was charged with being in the unlawful possession of a gold opal brooch.

Most interestingly, the Police also listed the personal property he had with him; a knife, a matchbox containing small stones and a walking stick. While the presence of the knife is fairly explanatory, the other two objects raise considerable thought. The walking stick may have been used to assist him with walking (perhaps indicating he suffered from an injury or limp) or it may have been used as an accessory which was common during this time. If the former, it calls into question his ability to travel long distances, some of which may have been on foot.

The matchbox on the other hand is curious. The stones must have been of some importance for them to be kept the way they were. This does not necessarily mean they had monetary value but they must have had some meaning. What were they? What was the significance to Alfred? Were the stones used as guides to identify various rocks? Were they simply a collection of interesting finds that he wished to keep?

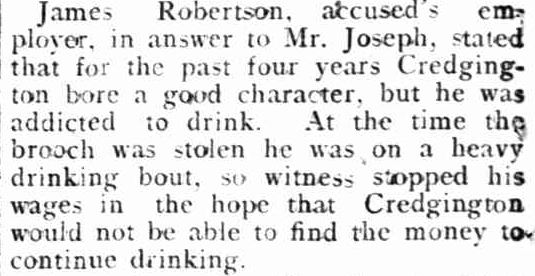

Alfred was brought to the Police Court that day and pleaded guilty before the Resident Magistrate Mr J. M. Finnerty. Where the Occurrence Book offers no further detail, the newspapers do. Headed ‘From Drink to Crime‘ Alfred’s employer, James Robertson, was called to give evidence as to his character.

The testimony must have helped. He was again discharged under the First Offender’s Act (I assume they did not know this had already been used at Mt Malcolm) and was ordered to repay twelve shillings and six pence to the pawnbroker he pawned the brooch too.

After this incident, Alfred left Boulder and headed north to Kookynie. Trouble again followed him and in November 1903 he was committed for trial, accused of garroting an engineer named Charles Sewell and stealing eight shillings and three pence from him. At the time there must have been an increase in garroting cases (strangling someone with the use of wire or cord) as the sensationalist newspaper ‘Truth’ declared there was a “garroting epidemic“. Alfred was once again acquitted.

![]()

While Alfred was travelling from place to place, trying to find his footing and getting into a little trouble with the Police, Ernest Bradbury was quiet. In fact, he was so unobtrusive that attempting to confirm where he came from has been incredibly difficult.

Of a similar age to Alfred, Ernest was also likely born in the late 1860s. His name was most often recorded as ‘Ernest Bradbury’ but some scant records indicate that his middle name was William. It appears to have been rarely used.

The presence of the middle name led me to wonder whether Ernest was the son of Samuel and Kezia Bradbury who was born in 1865 in Sydney, New South Wales. Research has shown however that there were many other Ernest Bradburys. Without any clues left behind by the Ernest Bradbury I’m researching, I’m reluctant to declare any of them as being the right one. Until such a time as more information is uncovered, Ernest’s story will simply have to start from when he first appeared on the goldfields.

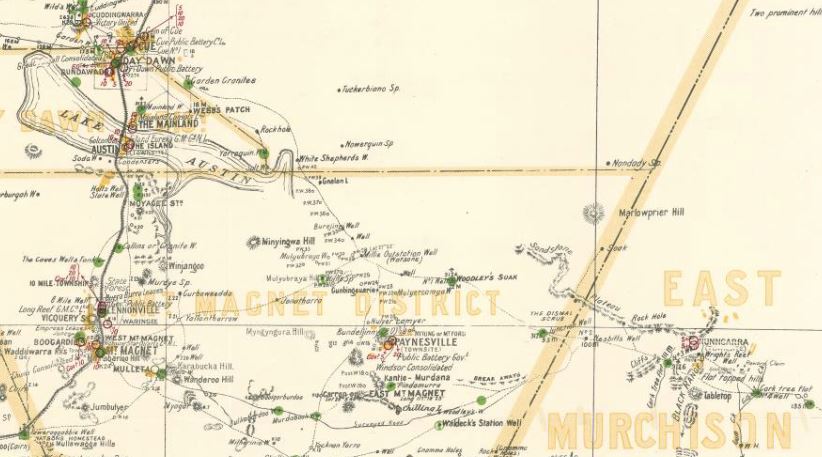

On 16 December 1903 an Australian Federal Election was held. There were five Western Australian electorates (Perth, Fremantle, Swan, Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie) and Ernest, prospecting on the goldfields at Yundamindera, fell within Coolgardie.

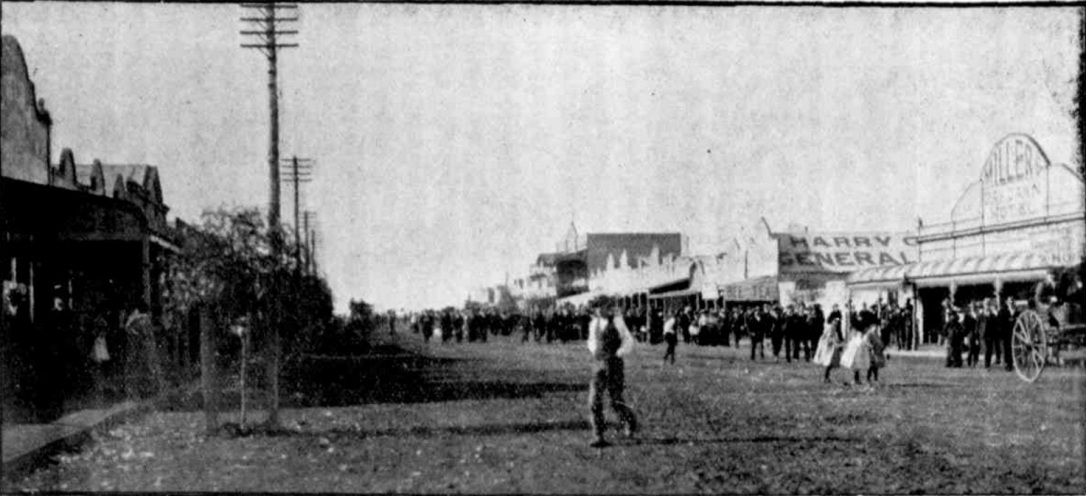

Yundamindera in 1903 consisted of Police quarters, a store, a butcher, a bank, a restaurant, several hotels and a Post Office. A small, quiet town servicing the miners in the area, the election may have made things somewhat more exciting with voting taking place at the Post Office. Ernest was listed on the roll (his surname incorrectly spelt Branbary) with his occupation recorded as ‘miner’.

Unlike Ernest, Alfred was not listed in the 1903 electoral roll. Having been acquitted of the garroting charge, it seems he was on the move again, heading northeast towards Laverton.

In the following year a Western Australian state election was held. Both Alfred and Ernest were recorded as living in the Mt Margaret district with Alfred at Hawk’s Nest working as a battery feeder and Ernest (again recorded as Branbary) still mining at Yundamindera.

Ernest was doing fairly well. The area he was mining was yielding some good gold and on 10 February 1904 an application was made for a mine site near Pennyweight Point which was east of Yundamindera. Four months later, on 1 June, it was granted. The mine was named ‘Problem‘.

With Alfred and Ernest essentially living on and working the same goldfields, it was inevitable that the two would eventually meet. While the details are unknown, how they met could be endlessly speculated. Perhaps both visited the town of Yundamindera at the same time and they got talking about Ernest’s new mine. Alfred may have been in need of a new job and Ernest may have given him one. Perhaps they had similar values and backgrounds and bonded over mutual experiences. Perhaps the fact that they were of similar age, height and looks was an ice breaker. Perhaps it was much simpler than any of the aforementioned notions and they became mates after a couple of drinks at the pub.

From 1905 Credgington and Bradbury stuck together. They had similar mining experience (Bradbury perhaps the more experienced of the two) and Credgington’s background as a jeweller and goldsmith would have also been useful. If you were spending countless hours working, socialising and travelling in the remote outback with another person you would really want to make sure you liked them. Clearly the friendship and partnership between Credgington and Bradbury worked well.

For the first time, indicating that he was settled at Yundamindera, Credgington appears listed in the 1905 Postal Directory. He gave his occupation as ‘miner’.

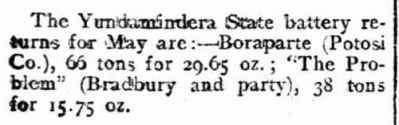

Throughout 1905 Credgington and Bradbury and perhaps several others worked the mine ‘Problem‘. Regular updates as to the rate of returns (showing the tons of rock processed and how much gold was extracted) were printed in various papers with the group (when mentioned) always referred to as ‘Bradbury and party‘. Like many others they utilised the state battery at Yundamindera.

Production data only shows for the year 1905 on the Department of Mines and Petroleum’s TENGRAPH database. The mine yielded 2.587kg. Nothing to sniff at but perhaps not the golden dream they were chasing. By 1906 the mine was at a standstill. The gold yield had decreased and it seems Credgington and Bradbury decided that it had produced all that it could. On 3 August 1906 it was declared dead.

The closure of ‘Problem‘ may have been disappointing however Credgington and Bradbury did not lose faith in the area. Throughout 1906 they remained in the Yundamindera district, working at Pennyweight. Both listed their occupations in the 1906 electoral roll as ‘prospector’.

Throughout 1907 and most of 1908, Credgington and Bradbury were quiet. There were no tiny references to them in the newspapers, no elections were held (so their names are not listed on electoral rolls) and neither of them appear in the Post Office Directories. It is doubtful they left the state so I assume they remained on the goldfields and continued with their prospecting efforts.

By 1908 they had given up on the Yundamindera district and travelled northwest to the goldfields at Youanmi.

Messrs. Bradbury and party have just applied for an 18-acre P.A., [Prospecting Area] half a mile south-east of the “White Boulder,” on which they are sinking a shaft on a 4ft reef of very nice looking quartz, with ironstone veins running through it. This is a continuation of the “Lingdale” lease, owned by Bowen and Spence. Messrs. Bradbury have about 20-tons of ore at grass, which will go from 12 dwt. to 14 dwt. per ton.

According to one newspaper, they were so impressed with what they were finding at Youanmi that they were not tempted by the new gold rush which was south at Youangarra.

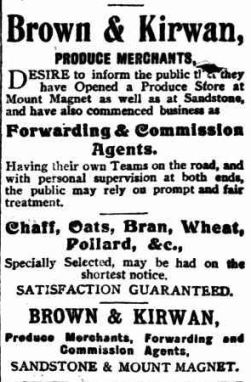

Around this time, and possibly while they were at Youanmi, they became acquainted with a teamster by the name of Herbert Hilton Australia Brown. Generally known as Hilton he also seems to have occasionally gone by the name George. Hilton was part owner in the business of Brown & Kirwan (merchants with offices based at Sandstone and Mount Magnet) and was involved in delivering goods to various areas on the goldfields. Another friendship and partnership was forged.

On 12 November 1908, Warden Clifton heard applications for prospecting areas, garden areas, residence areas, business areas and gold mining leases for the Sandstone district in the Sandstone Warden’s Court. Second on the list were Ernest Bradbury, Fred. Credgington and Hilton Brown for Prospecting Area number 317. Their request was granted.

Considering the timeline and the fact that they were located at Youanmi in the previous month it seems possible the Prospecting Area related to that goldfield. While I have not uncovered the application nor the Court records relating to their grant, oral evidence (provided over 20 years later) adds weight to this theory. Credgington and Bradbury were at Youanmi throughout all or part of 1908 and 1909 before making their way to Sandstone with Hilton Brown.

Both these men were prospecting around Youanne [Youanmi] in the early part of 1909 & later on in the same year they arrived at Sandstone in a camel team with George Brown, who was then a partner in the Produce store of Brown & Kirwan. [William Summers, carrier for Brown & Kirwan]

The prospecting dream had not yet ended and in the middle of 1909 they wrote from Sandstone to the Public Works Department at Day Dawn, requesting the loan of camels and equipment with the intention to head “north of Peak Hill and Lake Way (Wiluna).” Their request was granted.

The Sandstone railway line (which could have taken them to Day Dawn) was not yet completed so Credgington and Bradbury did not have the option of travelling by train. They decided to travel by camel. Having spent many years camping out in the bush, travelling by camel was probably preferred. Unlike other options, it meant they retained a great deal of freedom with regards to their destination and route taken.

With no camels of their own they turned to their friend Hilton. The business of Brown & Kirwan was not only run as produce merchants and carriers, they also often backed prospectors financially. Credgington and Bradbury took advantage of this and were given two camels as well as supplies.

There is no doubt they would have had some sort of agreement (be it verbal or written) with Brown & Kirwan. They interacted with William Summers (another person involved in the business) as well as Percy Gillam who was the Manager in charge of the accounts. Their supplies were paid for by the firm with Summers claiming years later that they were also financed to the tune of £1 per week. He could not say for sure whether they actually received any money before they left.

Remarkably, despite Credgington and Bradbury’s partnership and mateship, Hilton Brown, William Summers and Percy Gillam all claimed that they only really knew Bradbury. Two of them could not even remember Credgington’s name. Hilton, in particular, could only remember his broken nose.

While I acknowledge that the passing of time can result in fuzzy memories and the forgetting of names, I’m not entirely sure why none of them could remember Credgington. It raises the thought that perhaps it was Bradbury who took charge when it came to organising the supplies and Credgington only interacted with the men of Brown & Kirwan in passing. Then again, surely Hilton Brown knew him if he was equally involved in the previously mentioned Prospecting Area approved by the Sandstone Warden’s Court. Is there some sort of clue in this forgetfulness?

Credgington and Bradbury only expected to be away for six months. They departed Sandstone with their camels and supplies and, despite the confusion in later years about where they were going, it seems likely they headed straight to Day Dawn.

Reaching Day Dawn in July 1909, it’s doubtful they stayed long. A few days may have been spent having a decent rest, eating a good square meal, tending to the camels lent to them by Brown & Kirwan and perhaps stocking up on more supplies. They also did what they came to do and visited the Public Works Department to collect the three extra camels and equipment which were promised to them by the Government.

Two white bullock camels named Taylor and Butler and one red bullock camel named Ruby joined them on their prospecting trip. As well as being named, each camel had a particular set of identifying markers on their body (left). Credgington and Bradbury were also given the “necessary equipment” which included: three pack saddles, three pairs of hobble straps, three hobble chains, three bells, three bell straps and two camel head-stalls. Most interestingly, they were provided with two G.I. (galvanised iron) water drums which held 20 gallons each.

Two white bullock camels named Taylor and Butler and one red bullock camel named Ruby joined them on their prospecting trip. As well as being named, each camel had a particular set of identifying markers on their body (left). Credgington and Bradbury were also given the “necessary equipment” which included: three pack saddles, three pairs of hobble straps, three hobble chains, three bells, three bell straps and two camel head-stalls. Most interestingly, they were provided with two G.I. (galvanised iron) water drums which held 20 gallons each.

With their camels, supplies and equipment in tow, they departed Day Dawn on 19 July 1909, perhaps feeling hopeful that their new prospecting venture would be a success. There is no known photo of Alfred Credgington and Ernest Bradbury however they may have looked a little like the men in the below image who were also noted to be heading to new goldfields in 1905.

Their date of departure from Day Dawn was the last substantial piece of evidence. Everyone knew they left but no one knew where they went afterwards.

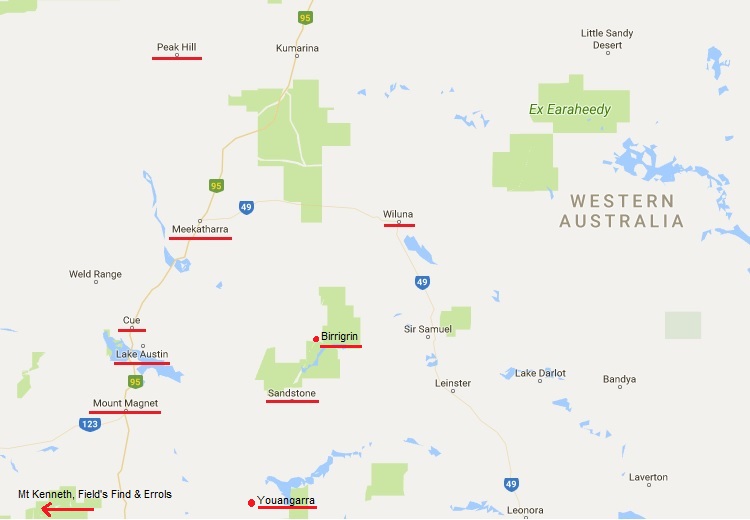

Turning to the Police interviews (which were conducted decades later) is not particularly helpful. Each person had a different opinion of where they thought they were going. Hilton Brown thought they were heading to Meekatharra for stores and then east to prospect around Lake Way near Wiluna. William Summers thought they may have gone towards Mt Magnet or to Birrigrin (complete opposite directions) and then to Meekatharra. While he was unsure of the direction they took, he knew they were eventually headed for Day Dawn and was the only person who thought they were intending to prospect around Lake Austin before returning to Sandstone.

The Government Public Works Department was much the same. They initially thought Credgington and Bradbury wanted the camels for prospecting north of Peak Hill and Lake Way (which incidentally are vastly different areas) but later stated that they thought they intended to prospect “from Curran’s Find S.W. [Youangarra] and thence west to Mount Kenneth via Field’s Find and Errols“.

According to Summers, nine months after Credgington and Bradbury left Sandstone (in approximately April 1910) concern that something had befallen them grew and a search was conducted which lasted several weeks. No trace of them was found. One of Hilton’s camels also eventually returned to Sandstone but I suppose they deemed it too far gone for a second search.

While I have no reason to believe Summers was lying with respect to the above statement, looking through the Police Occurrence Books for Sandstone and in the newspapers from around this time period shows no evidence of this fact. People missing in the outback or lost in the bush regularly made the news and were described in quite some detail. It seems extraordinary that a search on such a scale was not similarly reported and it is unusual that the Police did not record the event.

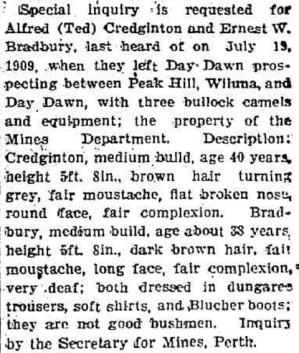

In April 1910 the Secretary for Mines (down three camels and equipment) realised they had heard nothing from Credgington and Bradbury since they left Day Dawn in the previous year. A special inquiry notice was placed in the Government Gazette and was reprinted in The Daily News under the heading ‘Local Inquiries’. It was one of 15 notices in the column which sought information relating to missing friends in Western Australia.

It is the most detailed description of Credgington and Bradbury. It shows they were similar looking, of similar age and stood at the same height (5ft 8in). Bradbury was described as “very deaf” while Credgington was described as having a “flat broken nose“. Both were dressed in dungaree trousers, soft shirts and blucher boots. No reference was made as to whether the boots were hob nailed. Furthermore, it was noted that they were “not good bushmen“. A description which, after having researched their time on the goldfields, seems at odds with their history. It was also the complete opposite of William Summers’ description of Bradbury whom he considered an “experienced bushman“.

In December 1910 the Secretary for Mines turned to the Commissioner of Police for help. While the Police could not shed any light on their whereabouts, on one of the documents someone wrote the tiniest of clues in small handwriting on the left hand side of the page.

It was reported that these men were seen prospecting near the 40 Mile on the Sandstone-Birrigrin Road in Nov ’09.

It is possible the sighting may have been incorrect however if it wasn’t, it shows that Credgington and Bradbury left Day Dawn and travelled east after all, prospecting around the Lake Mason area.

What happened next is anyone’s guess. If the skeletons found under the gum tree were indeed theirs, if would appear that at some point they headed back towards Lake Austin, perhaps to return the Government camels to the depot at Day Dawn. En route, they met their deaths, the cause of which were never ascertained but largely attributed to dehydration. It is a statement (especially now knowing that they had 20 gallon water drums with them) of which I am not convinced.

In analysing their stories, there is one record which is jarring. On 13 April 1910 an Australian Federal Election was held. Recorded as living at Sandstone and working as prospectors, were Ernest Bradbury and Alfred Credgington. To add more confusion, Ernest was further recorded as a miner at Yundamindera. Two main thoughts come to mind, with the first being, quite obviously, that they voted. The second is that there was some kind of mistake. Further research indicates that this could be possible. There were numerous issues with the 1910 electoral rolls which were compiled via house to house canvassing by the Police. Perhaps Police (being small in numbers in certain areas of the outback) could not spend time canvassing and thus used a previous years’ roll. However, if it was not a mistake, it turns the story and all that we know about their disappearance on its head.

Regardless, after this point, the names of Credgington and Bradbury disappear from records and newspapers until just over 20 years later when two skeletons were found at Lake Austin and Percy Gillam wrote his letter. Given all that we know, it is still probable that it was them.

Throughout my time researching this story I have constantly twisted and turned these facts in my mind, trying to see them from different angles in the hope that something new would stand out. There has been a general feeling of ‘something is missing‘ and ‘something doesn’t seem right‘. I am however missing far too many details and facts. I have spent numerous days and countless hours looking through records hoping to find a small glimpse of Credgington and Bradbury which could help pinpoint when and where they were. Nothing was found and, without a starting point, such research could go on forever.

It seems fitting that one of the principal objects found with the skeletons was a pocket watch, no longer telling the time but still managing to give a tick; a sign that time itself is eternal. Someone once knew something. Someone once held the all-important clue. The answers however may never come. Much like the skeletons at Lake Austin, time buried the answers in the red dirt of the outback. Year after year they slowly disintegrated until what was left of the story was only a fragment.

Sources:

- Heartfelt thanks to a descendant of the Credgington family who emailed me a copy of her article published in The Australian Family Tree Connection magazine (February 2014 – Pages 14-17) as well as a copy of a document which I did not see at the State Records Office of WA.

- First verse of Henry Lawson’s poem, ‘To An Old Mate’ courtesy of the Australian Poetry Library (https://www.poetrylibrary.edu.au/poets/lawson-henry/to-an-old-mate-0002001).

- State Records Office of Western Australia; Western Australia Police Department; General Files [2]; Reference: AU WA S76 – cons430 1930/9342; Title: ‘Skeletons of two white men found near Lake Austin (Cue) on 26/11/1930.’

- State Records Office of Western Australia; Western Australia Police Department; General Files [2]; Reference: AU WA S76 – cons430 1910/5846; Title: ‘Prospectors – Alfred Credgington [Credington?] and E. Bradbury with 3 camels (Hired?) equipment left Day Dawn 19.7.1909.’

- State Record Office of Western Australia; Western Australia Police Department; Boulder Police Station; Occurrence book (1901-12-05 – 1902-05-22); AU WA S3577- cons 1299 009.

- State Library of Western Australia; Map of the Central Goldfields [cartographic material] : including parts of Murchison, East Murchison, Yalgoo & Peak Hill G.Fs.; Call Number: 9022.M95H2 (http://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b2247326_2).

- PRIZE LIST.,Otago Daily Times, Issue 4938, 14 December 1877 (http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ODT18771214.2.16).

- 1888 ‘Advertising’, Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 – 1918), 28 April, p. 8. , viewed 15 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article88548252

- Ancestry.com. New Zealand, Electoral Rolls, 1853-1981 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: New Zealand Electoral Rolls, 1853–1981. Auckland, New Zealand: BAB microfilming. Microfiche publication, 4032 fiche.

- Bendigo and vicinity : a comprehensive history of her past, and a resume of her resources ; together with the biographies of her representative pioneers, public, commercial, and professional men / compiled by W.B. Kimberly.; Niven; 1895.

- 1896 ‘SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE.’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 11 July, p. 4. , viewed 17 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3095774

- 1898 ‘DEPARTURES.’, Albany Advertiser (WA : 1897 – 1950), 22 January, p. 3. , viewed 17 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article69902265

- 1897 ‘Classified Advertising’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 8 June, p. 2. , viewed 17 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3113269

- 1898 ‘MT. MALCOLM.’, The Menzies Miner (WA : 1896 – 1901), 3 December, p. 18. , viewed 17 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article233061017

- 1899 ‘MINING NEWS.’, Coolgardie Miner (WA : 1894 – 1911), 12 July, p. 6. , viewed 22 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217346939

- 1899 ‘MINING NEWS.’, Coolgardie Miner (WA : 1894 – 1911), 5 August, p. 3. , viewed 22 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217349026

- 1899 ‘MINING NEWS.’, Coolgardie Miner (WA : 1894 – 1911), 8 August, p. 3. , viewed 22 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217349244

- 1900 ‘Advertising’, Westralian Worker (Perth, WA : 1900 – 1951), 14 December, p. 8. , viewed 22 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article148299088

- 1902 ‘BOULDER POLICE COURT.’, Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 – 1950), 24 February, p. 4. , viewed 24 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article89042061

- 1903 ‘Random Remarks’, Truth (Perth, WA : 1903 – 1931), 21 November, p. 1. (CITY EDITION : SUPPLEMENT), viewed 24 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207386206

- 1903 ‘KALGOORLIE CIRCUIT COURT’, Coolgardie Miner (WA : 1894 – 1911), 3 December, p. 3. , viewed 24 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217420479

- 1903 ‘Advertising’, Coolgardie Miner (WA : 1894 – 1911), 12 December, p. 2. , viewed 24 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article217420926

- 1904 ‘No Title’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 23 August, p. 22. , viewed 24 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32207767

- Australian Electoral Commission; Western Australia, Electoral Rolls (1903-1980); 1903 (Coolgardie-Yundamindera); 1906 (Coolgardie-Yundamindera);

- Australian Electoral Commission; Western Australia, Electoral Rolls (1904); Mt Margaret. Obtained via Outback Family History database (http://www.outbackfamilyhistory.com.au/records/index.php?category=People&subcategory=Electoral%20Roll)

- State Library of Western Australia; The Western Australian Directory [Wise’s] 1905; Viewed online (http://slwa.wa.gov.au/explore-discover/wa-heritage/post-office-directories/1905).

- 1905 ‘MINING NOTES.’, Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 – 1950), 8 June, p. 3. , viewed 31 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article89206984

- Department of Mines and Petroleum; TENGRAPH Database; Problem; Tenement GML3100726.

- 1904 ‘No Title’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 23 August, p. 23. , viewed 03 Sep 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32207724

- 1908 ‘YOUANME.’, The Black Range Courier and Sandstone Observer (WA : 1907 – 1915), 23 October, p. 2. , viewed 31 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201951435

- 1908 ‘Youanme Mining.’, The Black Range Courier and Sandstone Observer (WA : 1907 – 1915), 30 October, p. 3. , viewed 31 Aug 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201951454

- 1911 ‘No Title’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 28 November, p. 20. , viewed 01 Sep 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33400104

- 1909 ‘Advertising’, The Black Range Courier and Sandstone Observer (WA : 1907 – 1915), 16 July, p. 4. , viewed 01 Sep 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204877810

- Image of the camel team at Southern Cross courtesy of the State Library of Western Australia (Call Number: 013929PD). http://purl.slwa.wa.gov.au/slwa_b2940835_010

- 1927 ‘Sailors and Soldiers Section’, Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 – 1954), 9 October, p. 7. , viewed 04 Sep 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58335794

- 1905 ‘No Title’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 26 September, p. 20. , viewed 05 Sep 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33022727

- 1905 ‘No Title’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 16 May, p. 26. , viewed 05 Sep 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33020684

- 1910 ‘LOCAL INQUIRIES.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 16 April, p. 4. (THIRD EDITION), viewed 06 Sep 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article77829274

Very good Jessica very well written

LikeLike

Thank you Sandra. 😊

LikeLike

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2017/09/friday-fossicking-22nd-september-2017.html

Thank you, Chris

LikeLike

Thanks Chris. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Would it be possible yo get DNA from the 2 skeletons found? There must be rellies. It woud be great to get the identities of the two skeletons. What a story! My partner’s mum was a Bradbury but that is a very common name I have found. What a great job you have done.

LikeLike

It could be possible if we knew where they were buried. Unfortunately, they were reburied under the tree where they were found and no records indicate where it was on Lake Austin.

LikeLike

Am interested in the life and former whereabouts and activities of Alfred C’s elder brother Herbert Credgington.

LikeLike